Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Standard lexical sets

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

80-7

19-3-2022

3899

Standard lexical sets

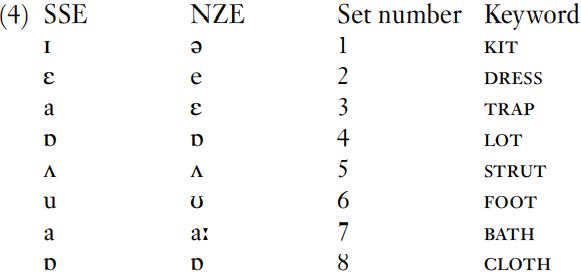

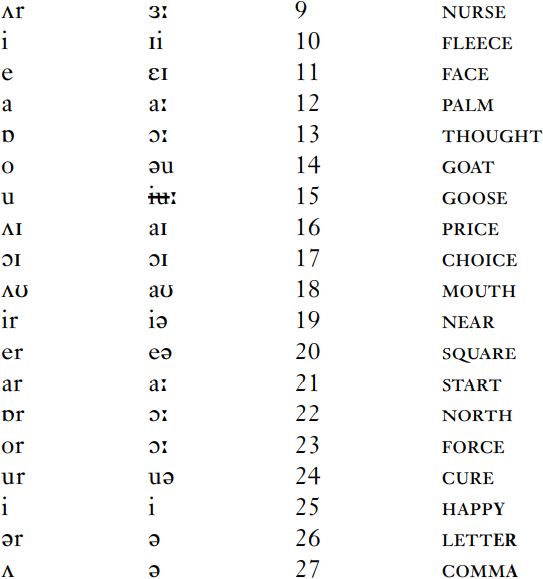

The oppositions established for SSBE in (1) and (2) cannot, then, be transferred automatically to other accents. For instance, General American has no centring diphthong phonemes; leer, lair and lure have the /i:/, /eI/ and /u:/ vowels of beat, bait and boot, followed in each case by /r/. GA also lacks the /ɒ/ vowel of SSBE pot; but we cannot assume that all the words with /ɒ/ in SSBE have a single, different phoneme in GA. On the contrary, some words, like lot, pot, sock, possible have GA /ɑ:/ (as also in palm, father, Bart, far in both accents); but others, including cloth, cough, cross, long have GA /ɔ:/ (as also in thought, sauce, north, war in both accents).

It follows that lists of minimal pairs are suitable when our goal is the establishment of a phoneme system for a single accent; but they may not be the best option when different accents are being compared. An alternative is to use a system introduced by John Wells (see Recommendations for reading), involving ‘standard lexical sets’, as shown in (3). The key word for each standard lexical set appears conventionally in capital letters, and is shorthand for a whole list of other words sharing the same vowel, although the precise vowel they do share may vary from accent to accent.

These lexical sets allow comparison between accents to be made much more straightforwardly: we can now ask which vowel speakers of a particular accent have in the KIT set, or whether they have the same vowel in NORTH and FORCE (as SSBE does) or two different vowels (as GA does). We could add that many speakers of Northern English will have /υ/ in STRUT as well as FOOT, and /a/ in BATH as well as TRAP, pinpointing two of the differences most commonly noted between north and south. The point of the standard lexical sets is not to show that oppositions exist in all these contexts: in fact, there may be no accent of English which contrasts twenty-seven phonemically different vowels in the twentyseven lexical sets (or even twenty-four, for the stressed vowels). Instead, the aim is to allow differences between accents (and sometimes between speakers of the same accent, perhaps in different generations) to be pinpointed and discussed.

More detail on accent variation will be given in the next chapter. For the moment, to illustrate the usefulness of the standard lexical sets, the vowels of two further accents are given in (4). Standard Scottish English (or SSE) is the Scottish equivalent of SSBE: a relatively unlocalised, socially prestigious accent. Many middle-class Scots have SSE as a native variety; many others use it in formal situations, and it is widely heard in the media, in education and in the Scottish Parliament. It is to be contrasted with Scots, sometimes called ‘broad Scots’, a divergent range of non-standard Scottish dialects which differ from English Standard English not only in phonetics and phonology, but also in vocabulary and grammar. The final example is New Zealand English, a relatively recent variety which shares some characteristics with the other extraterritorial Englishes spoken in Australia and South Africa, but also has some distinctive characteristics of its own, notably the fact that schwa appears in stressed position, in the KIT lexical set.

A number of differences between these accents, and between each of them and SSBE or GA, can be read off these lists. For instance, SSE does not contrast the TRAP and PALM vowels, so that Sam and psalm, which are minimal pairs for all the other varieties considered so far, are homophonous for Scottish speakers, both having short low front /a/. In NZE, Sam and psalm do form a minimal pair, but not with low short front /a/ or  versus low long back /ɑ:/: instead, in NZE we find mid short front /ε/ as opposed to low long back front /a:/. Both the TRAP and DRESS vowels in NZE are higher than those of SSBE or GA, while the long vowels of FLEECE, FACE, GOAT and GOOSE are very characteristically diphthongs.

versus low long back /ɑ:/: instead, in NZE we find mid short front /ε/ as opposed to low long back front /a:/. Both the TRAP and DRESS vowels in NZE are higher than those of SSBE or GA, while the long vowels of FLEECE, FACE, GOAT and GOOSE are very characteristically diphthongs.

Recall, however, that phonemes are abstract units, and thus could potentially be symbolized using any IPA, or indeed any other character. The symbols chosen for particular phonemes in the lists above are not the only possibilities; they reflect a choice made by a particular phonologist. I have elected to use a symbol for each phoneme, in each accent, which corresponds to one of the main allophones of that phoneme: that is, in many cases speakers of the accent in question will actually pronounce the symbol given in the list, with its normal IPA value. Thus, NZE speakers will often say [ε] in trap, and [e] in dress, and will typically have a diphthongal pronunciation of fleece, goose, goat and face. However, for some phonologists the symbols used in (4) would not be the most obvious choices. This highlights a decision phonologists must make in establishing a phoneme system. On the one hand, we may wish our phonemes to be fairly concrete, reflecting quite closely what speakers actually do in at least some of their everyday pronunciations; this is the choice made here. It follows that there will be significant symbol differences between the vowel systems of different accents. On the other hand, some phonologists feel it is more important to reflect the fact that English is a single language, and believe that speakers must have common mental representations to allow them to understand one another, even if they speak rather different accents. In that case, common phoneme symbols might be chosen. For instance, instead of using /Ii/ for FLEECE in NZE, we would select /i:/, stressing that this is the same phoneme as in SSBE or GA, although there would then have to be an allophonic rule to say that this phoneme is very typically diphthongised for most New Zealanders.

The second solution has the advantage that it stresses the common features speakers of English might share, at least in terms of mental representations, although they may sound very different in actual conversation. It therefore maintains a strong difference between abstract phonology, and concrete phonetics: the /a/ phoneme in TRAP would be low [a] for SSBE, but low mid [ε] for NZE, while the /ε/ phoneme of DRESS would be high mid [e] for NZE, and low mid [ε] in all the other accents we have examined, meaning that phonemes potentially have very different realizations, and the same realization can belong to different phonemes in different accents. At this point, we do not know enough about how speakers store and process their language mentally to prove which is the most appropriate solution; but it is worth asking how speakers would learn a very abstract system, which does not reflect the phonetic qualities they hear around them during language acquisition.

If a New Zealander pronounces the FLEECE vowel as a diphthong, and hears NZE or Australian English (which also tends to have a diphthong here) much more often than British or American accents, why would such a speaker assume this vowel phoneme should be stored as anything other than a diphthong? And why should the ‘right’ value for the phoneme corresponds to what is pronounced in British or American English, rather than in New Zealand or Australia? The decision between representations which are close to phonetic reality, but with considerable accent variation and potentially rather messy systems, or rather abstract phonemes, with streamlined and economical systems unifying the speakers of different varieties, must be confronted whenever we move away from surface phonetics and into phonology. In this book, I shall continue to use phoneme symbols which correspond to major allophones of those phonemes in the accent concerned; but other, more abstract alternatives can be found in the recommended further reading.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)