A warning note on phonological rules

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

48-4

الجزء والصفحة:

48-4

17-3-2022

17-3-2022

1490

1490

A warning note on phonological rules

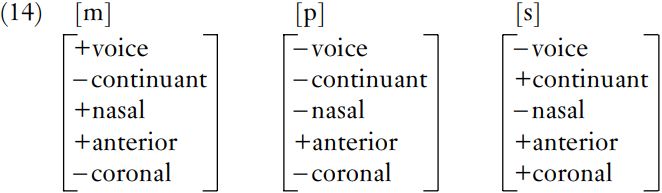

Paradoxically, phonological rules are not rules in one of the common, everyday English meanings of that word; they are not regulations, which spell out what must happen. Instead, they are formal descriptions of what does happen, for speakers of a particular variety of a particular language at a particular time. Some phonological rules may also state what sometimes happens, with the outcome depending on issues outside phonology and phonetics altogether. For example, if you say hamster slowly and carefully, it will sound like [hamstə] (or [hamstəɹ], depending on whether you ‘drop your [r]s’ in this context or not. If you say the word quickly several times, you will produce something closer to your normal, casual speech pronunciation, and it is highly likely that there will be an extra consonant in there, giving [hampstə] (or [hampstəɹ] instead. As the rate of speech increases, adjacent sounds influence one another even more than usual, because the same complex articulations are taking place in even less time. Here, the articulators are moving from a voiced nasal stop [m], to a voiceless alveolar fricative [s], so that almost every possible property has to change all at once (apart from the source and direction of the airstream, which all English sounds have in common anyway). In fast speech, not all these transitions may be perfectly coordinated: the extraneous [p] appears when the speaker has succeeded in switching off voicing, and raising the velum to cut off airflow through the nose, but has not yet shifted from stop to fricative, or from labial to alveolar. There is consequently a brief moment when the features appropriate for [p] are all in place, before the place and manner of articulation are also altered to produce the intended [s]. Listing the feature composition of [m], [p] and [s], as in (14), reveals that [p] shares half the features of each of [m] and [s], so it is entirely understandable that [p] should arise from this casual speech process.

A very similar process arises in words like mince and prince, which can become homophonous (that is, identical in sound) to mints and prints in fast speech. Here, the transition is from [n], a voiced alveolar nasal stop, to [s], a voiceless alveolar oral fricative, and the half-way house is [t], which this time shares its place of articulation with both neighbors, but differs from [n] in voicing and nasality, and from [s] in manner of articulation. In both hamster and mince/prince, however, the casual speech process creating the extra medial plosive is an optional one. This does not mean that it is consciously controlled by the speaker: but the formality of the situation, the identity of the person you are talking to, and even the topic of conversation can determine how likely these casual speech processes are. In a formal style, for instance asking a question after a lecture, or having a job interview, you are far more likely to make a careful transition from nasal to fricative in words of this kind, while informal style, for instance chatting to friends over a drink, is much more conducive to intrusion of the ‘extra’ plosive. These issues of formality and social context, which are the domain of sociolinguistics, are not directly within the scope of phonetics and phonology, although they clearly influence speakers’ phonetic and phonological behavior.

If speakers of English keep pronouncing [hampstə] and [prnts] prince in sufficient numbers, and in enough contexts, these pronunciations may become the norm, extending even into formal circumstances, and being learned as the canonical pronunciation by children (this is exactly what has already happened in bramble, and the name Dempster). Even now, children (and occasionally adults too) spell hamster as hampster, showing that they may believe this to be the ‘correct’ form. Developments from casual to formal pronunciation are one source of language change, and mean that phonological rules and systems can vary between languages, and can change over time. For instance, as we saw earlier, modern English has a phonemic contrast between /f/ and /v/, but in Old English, [f ] and [v] were allophones of a single phoneme, /f/.

No feature system is perfect; however carefully designed a system is, it will not in itself explain all the properties of a particular language, which may sometimes reflect quirks and idiosyncrasies which have arisen during the history of that system. Equally, some developments of one sound into another are perfectly natural in a particular context, but the feature system fails to express this transparently because it is so closely linked to articulation: voiceless sonorants are rare simply because they are rather difficult to hear, and the best possible features, if they lack an acoustic aspect, will fail to reflect that fact. Just as we are all speakers and hearers, so sounds have both articulatory and acoustic components: sometimes one of these is relevant in determining allophonic variation, sometimes the other – and sometimes both. For instance, it is quite common cross-linguistically for labial sounds, like [p] or [f ], to turn into velar ones, like [k] or [x], and vice versa: in words like cough, the originally signaled a velar fricative, [x], which has historically become [f ]. In articulatory terms, labials and velars have little in common: indeed, they are produced almost at opposite ends of the vocal tract. We can at least use [–coronal] for the composite set of labials and velars; but this would also, counterfactually, include glottals; and in any case, negative definitions are of limited usefulness (why should two classes of consonants work together because both do not involve the front of the tongue?). However, acoustic analysis reveals a striking similarity in the profile of energy making up labials and velars, so that the two categories are heard as more similar than we might expect. In addition, the vowel in cough is pronounced with rounded lips; if this lip-rounding is carried on just a little too long, so that it affects the following consonant, the articulators will also be in a position appropriate for [f ]. In this case, articulatory and acoustic factors have worked together to change the [x] of earlier English to the [f ] we find today.

Most phonological feature systems are based uniquely either on articulatory or on acoustic factors: either way, we would miss part of the story in a case like this.

However, adopting a feature system of one sort or another is invaluable in formalizing phonological rules; in sharpening up our thinking when formulating such rules; in seeing segments like [p] or [s] as shorthand for a bundle of properties, rather than as mysterious, self-contained units; and in trying to explain why certain sounds and groups of sounds behave in the way they do.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة