Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Adverbial diagnostics

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

62-4

14-2-2022

1766

Adverbial diagnostics

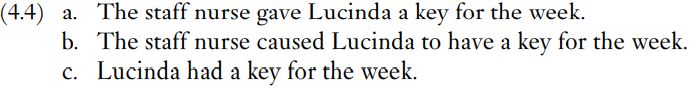

Consider (4.4a). (Perhaps Lucinda is an anesthetist who needed access to a particular store-room for the week in question.) Example (4.4a) entails (4.4b), a causative construction, and I am going to suggest that (4.4a) is itself a causative construction, even though it lacks an embedded clause. Tenny (2000) proposes that a justification for this sort of claim can be found by looking at what is modified by certain adverbials, such as the preposition phrase for the week in (4.4a).

Because (4.4b) is a causative fitting the pattern to the left of the entailment arrow in (4.3), we should expect (4.4b) to entail (4.4c), and intuitively it does.

Giving is not the only way of causing someone to have something; a malicious individual who “plants” an incriminating key on Lucinda would also ‘cause her to have’ it. So, while (4.4a) entails (4.4b), the entailment does not go in the reverse direction: starting from knowledge that (4.4b) is true would not guarantee that (4.4a) is true. Recall that a one-way pattern of entailment, with the rest of the sentence kept constant, defines the semantic relationship of hyponym to superordinate. Give is a hyponym of cause … to have.

There are several possible interpretations available for (4.4a), but on the most obvious one the staff nurse gave Lucinda a key once and Lucinda retained possession of it for the week. On this interpretation, what does for the week have its modifying effect on? A reasonable answer is seen in the entailed sentence (4.4b), where for the week modifies the clause with have to indicate how long Lucinda had the key. The modifier does its work on the meaning carried by the entailed clause, the one describing the caused situation.

If we think of the verb cause in (4.4b) as describing a single event4 in which the staff nurse hands over a key to Lucinda (or “plants” it in Lucinda’s coat pocket), then that is likely to take only seconds and it would be implausible to think that for the week says how long that event lasts. It is the same with (4.4a): if for the week modifies give as a handing-over event, then the situation is far-fetched: the staff nurse very, very slowly takes up the key and – over a period of days – passes it across to Lucinda. For the ordinary way of understanding (4.4a), it is reasonable to say that the durational preposition phrase for the week does not modify the handing over, but instead modifies an “understood” embedded situation ‘Lucinda to have a key’, and the effect of this modification can be expressed by (4.4c).

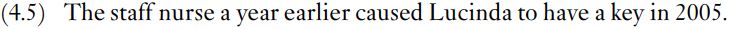

In a sentence like (4.4b), as well as adverbial modification operating on the embedded situation clause – the clause with have – there could be separate adverbial modification on the main clause – the one with the causative verb cause – as exemplified in (4.5).

The sentence in (4.5) is a possible way of talking about a staff nurse doing something in 2004 – perhaps through inattention misplacing a key – and Lucinda, who might never have had any interaction with that staff nurse, getting the key a year later, for example taking it from where it is hanging on the wrong hook in the hospital ward’s key cupboard. Whatever the scenario, the point is that two-clause causatives like (4.4b) and (4.5) can be used to describe indirect causation: someone does something and – perhaps unintentionally; maybe after a long interval – causes a situation which can be traced back to that person’s act. By contrast, a one-clause causative, such as The staff nurse gave Lucinda a key, describes direct causation, so (4.4a) is not suitable for expressing Lucinda getting a key in an event that was caused by an act distant in time and not intended to result in her having the key.

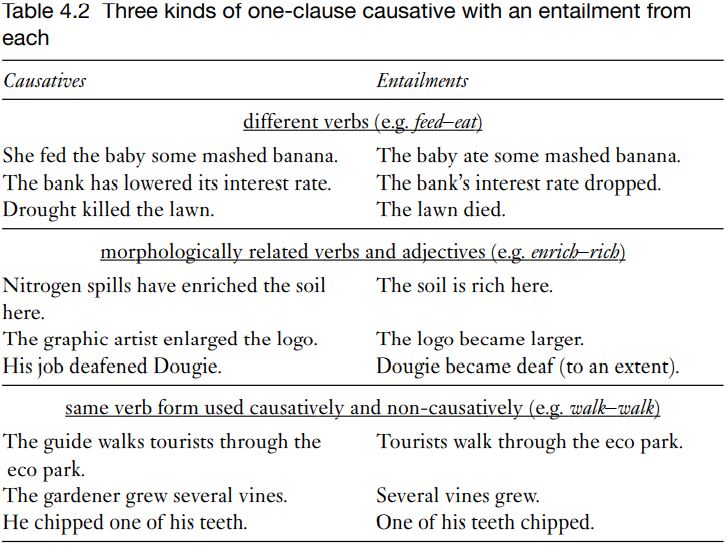

In Table 4.1 the causative sentences each had an overt embedded clause. But in Table 4.2 the causative sentences are like (4.4a) in having only one clause syntactically, though for each of them there is an entailed proposition about a caused situation – an entailment that could be expressed by means of the corresponding sentence in the right-hand column of Table 4.2. In view of these entailments, it is reasonable to call the sentences in the left-hand column causative. And bearing in mind the relationships illustrated in (4.4a–c), the entailed propositions can be taken as “understood” embedded situations in the causatives.

Imagine that a brand new bank starts business offering a low interest rate on its credit card accounts. A year later difficult financial circumstances obliges it to raise its interest rate. After a few months it proves to be possible to drop the rate back to its original level. Notice, in the scenario just sketched, that this bank’s rate is decreasing for the first time ever. Nonetheless, this first fall can be reported as The bank has lowered its interest rates again. There are other ways of wording the report, but – perhaps surprisingly – it is possible to use the adverb again. This use of

again is called restitutive: there is restitution of a previously existing state (Tenny 2000). For the case in question, the rate was low, then it rose, then it was low. Because it had been low before, it is appropriate to use again even to describe the first ever decrease in the rate. This is a reason for thinking that part of the meaning of the bank sentence is an embedded proposition which is not syntactically visible as an embedded clause. When there is reversion back to an earlier state, the restitutive adverb again can operate on the embedded situation, and this is evidence that the embedded situation is part of the meaning of the clause.

To be considered next are differences between the entailed sentences in the right-hand column of Table 4.2 in terms of the number and types of arguments demanded by their verbs. The first sentence The baby ate some mashed banana is the only one that is transitive, which is to say that it is a clause with a subject argument (The baby) and a direct object argument (some mashed banana). Tourists walk through the eco park also has two arguments (You and through the eco park) but, because of the preposition through, the constituent through the eco park is not a direct object; so the sentence is intransitive, rather than transitive. Other intransitive sentences here are The bank’s interest rate dropped, The lawn died, Several vines grew and One of his teeth chipped. They will be discussed soon. The other sentences on the right in Table 4.2 have copula verbs, be or become (see Miller 2002: 30–2). Semantically, these copula sentences indicate that the referent of the subject belongs in a category that is often labelled by an adjective, for instance The soil is rich here designates the soil here as being in the category ‘rich’; likewise, for the logo coming into the subcategory of ‘larger (things)’ and Dougie becoming ‘deaf (to an extent)’.

Intransitive clauses have been divided into two rather opaquely-named kinds (Trask 1993: 290–2) on the basis of the kind of the subject argument that their verbs require:

• An unergative verb requires a subject that is consciously responsible for what happens. Walk is such a verb and Tourists walk through the eco park is an unergative clause. A good test is acceptability with the adverb carefully, because taking care is only a possibility when an action is carried out deliberately. Tourists carefully walk through the eco park is unproblematic.

• Unaccusative verbs are seen in The bank’s interest rate dropped, The lawn died, Several vines grew and One of his teeth chipped. These intransitives will not easily take the adverb carefully: *The bank’s interest rate carefully dropped, *The lawn carefully died, *Several vines carefully grew, *One of his teeth carefully chipped. Even if the subject argument is a human being, the sentence will be peculiar when carefully is put into construction with an unaccusative verb, for example *Mort carefully died. With an unaccusative verb, the subject is affected by the action but does not count as responsible for it.

The last two lines of Table 4.2 show causatives entailing unaccusatives with the same verb form: Gardeners grow vines ⇒ Vines grow; He chipped a tooth ⇒ A tooth chipped. Fellbaum, who has done extensive studies of English vocabulary, says there are thousands of such pairs (2000: 54). Some more are listed in (4.6).

With the verbs in (4.6) a systematic semantic connection – causative-to-unaccusative entailment – is paralleled by a morphological link, in this case no change (also called conversion or zero derivation), as in He spilt the coffee ⇒The coffee spilt. Regular patterns like this prompt the search for similar semantic ties even when the word forms are unrelated, as with kill and die in Table 4.2.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)