Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Criteria for roles

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

120-11

3-2-2022

1761

Criteria for roles

A major question is how we decide how many roles are needed in the analysis of a given language. The central point is that, while intuitions may be the starting point of the analysis, the central criteria are grammatical (syntactic or morphological) or question–answer pairs such as those used below. A participant role that is not supported by grammatical criteria is suspicious. We do not deny appeal to intuitions nor the fact that for a given language some speakers will agree some of the time about some intuitions. But intuitions are not infallible, are not always shared and do need to be justified by evidence.

Another important point that must be mentioned here is that grammatical evidence allows only very general distinctions of meaning to be made. We will find ourselves working with very general roles, but the interpretation of any given clause combines information from the syntactic structure, including roles, information from the lexical verb and information from the lexical nouns inserted into a given structure. In the discussion that follows, roles are treated as assigned to nouns; since nouns are the heads of noun phrases, the property of being an Agent or Patient, say, spreads from nouns to the noun phrases that they head.

We begin with the simplest sort of example, as in (5)–(6).

In (5), baby is an Agent and biscuit is a Patient. Since it is not so obvious what role is to be assigned to baby in (6), we will leave the role undecided for the moment. What is important is that there are tests in English that distinguish the constructions in (5) and (6): (5), but not (6), is an appropriate answer to the question in (7).

The above question enables us to sort out events from states, since only sentences describing events can answer the question What happened? The questions in (8) and (9) pick out Agent and Patient.

In (8), X can be replaced by the baby: What did the baby do? He/she chewed the biscuit. In (9), X can be replaced by the biscuit: What happened to the biscuit? The baby chewed it. Example (6) is not an appropriate answer to either (8) or (9).

Other tests for Agent are available in English. One test is whether a clause can be incorporated into the WH cleft construction What X did was/What X is doing is and so on. For example, (5) can be incorporated in the construction to yield (10).

Other tests are whether the verb in a given clause can be put into the progressive or into the imperative. Example (5) meets both of these criteria, as shown in (11) and (12).

These tests are weaker because they are also met by verbs that denote states: The patient is suffering a lot of pain, You will soon be owning all the land round here. (The last example is from a TV play.) (Note that The patient is suffering a lot of pain is bizarre as an answer to What is the patient doing? (Compare annoying the nurses, complaining about the food and so on.)

Examples (13)–(15) introduce other roles.

In (13), Surrey has the role of Place; it denotes the location of Hartfield House. In (14), Kingston has the role of Goal, in that it denotes the goal of Mr Knightley’s journey, while in (15) Shropshire denotes the starting point, or source, of the journey and has the role of Source. Compare the examples in (16) and (17)

Example (16), like (14), contains the preposition to. Like (14), it describes movement, in the sense that the piano moves from a shop or warehouse to beside Jane Fairfax. This parallel is captured by assigning Jane Fairfax the role of Goal. Of course, the movement of a possession to its owner is not exactly the same as the movement of a person or vehicle to a destination, but this does not require different roles. Different interpretations will result from the different lexical verbs and lexical nouns.

Similarly, the analogy between (15) and (17) leads us to assign the role of Source to Frank in (17). The sentence presents the piano as starting its journey from Frank (whether that is literally true or not), just as Eleanor and Marianne started their journey from Shropshire. The important element in the analysis is not just that we can unpack the meanings of the sentences in each pair and discover parallels, but the occurrence of the same preposition in (14) and (16), and in (15) and (17). Important too is the fact that in many languages the equivalents of (14) and (16), and (15) and (17), contain the same preposition or case affix.

Other roles are illustrated in (18)–(19).

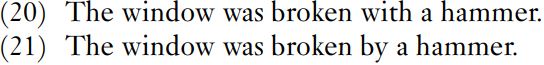

Hammer in (18) has the self-explanatory role of Instrument, although we will argue below that Instrument is a subtype of a more general role. Instruments are signaled by with in English, and a contrast is possible between passive sentences such as those in (20) and (21). (Typically the Instrument role is played by inanimate objects such as hammers and saws, but it could be played by an animate being in unusual situations: Bond smashed the window with his opponent. The general construction and the preposition with impose the Instrument role; the attachment of a human noun to that role is unusual, but the properties of the noun do not force the role to change.)

Example (20) is appropriate to a situation in which someone has picked up the hammer and used it to break the window. The Agent is not mentioned explicitly, but the occurrence of with signals the Instrument status of hammer and the presence of an unspecified Agent. Example (21) describes a situation in which, say, the hammer is balanced on a shelf beside the window but falls off ‘of its own accord’ and breaks the window

There is no Agent to be specified, and (21) indeed presents the hammer as the Agent through the occurrence of by. In (19), Mrs. Smith has the role known generally as Benefactive, the person who benefits from an action. Benefactive is signaled by for. Some analysts treat Benefactive as a subtype of Goal: this relates it to the movement phrase head for London.

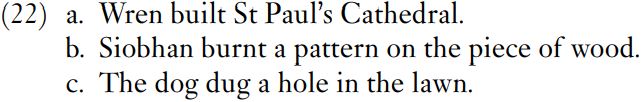

The direct objects in (22a–c) also raise the question of extra roles.

The question arises because it has been suggested that the direct object NP is not a Patient but rather a Result; this role would capture the fact that verbs such as build and dig denote actions which bring things into existence, rather than actions carried out on already existing things. It is true that the sentence What did X do to Y? cannot be appropriately answered by any of (22a–c). However, this is because the question can only be asked concerning things that exist already, and information in the lexical entry for build will specify that it relates to bringing things into existence. Moreover, ‘result’ noun phrases behave grammatically like Patient noun phrases; they function as direct object in active sentences; they function as subject in passive sentences. (Compare The hole was dug in the lawn by the dog and so on). Clauses containing ‘result’ noun phrases can be incorporated into WH clefts as in (10), What the dog did was dig a hole in the lawn. The grammatical evidence suggests that we are dealing with Patient noun phrases; the ‘result’ component of the meaning conveyed by (22a–c) can be derived from the meaning of the verbs BUILD, BURN and DIG, and no extra role is needed.

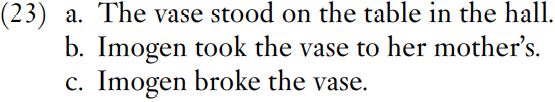

Another role that has been proposed is that of Theme, a role that is neutral with respect to Agent and Patient and is assigned to noun phrases such as the vase in (23a) and (23b).

In (23b), the vase is the direct object of took. The vase does not change its state, as it does in (23c), but merely its location. This semantic difference is not reflected in any grammatical properties (or at least not major ones) and can be captured in the information in the lexical entries for take and break. The role of Theme is not necessary

What of vase in (23a)? The sentence clearly does not describe an action, since it is not an answer to questions such as What happened? or What was happening? Nor does it answer questions such as What did the vase do? or What happened to the vase? (We assume that the sentence is not metaphorical and does not describe the vase taking up its stance on the table.) Example (23a) describes a state, but what role should be assigned to vase? By the same token, (6) describes a state too: what role is appropriate for baby? The grammar of English remains neutral in this respect, and we will treat vase in (23a) and baby in (6) as merely being neutral between Agent and Patient.

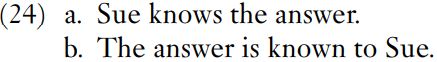

Certain verbs and adjectives denoting states do require a different role for subject nouns, as shown by (24).

Example (24a) is not an answer to the question What does Sue do? or to the question What is happening to Sue? The paraphrase in (24b) shows that to is a possible preposition in the passive, which in turn indicates that Sue does not simply have the Neutral role. Many accounts of participant roles propose the role of Experiencer, the label reflecting the notion that (24a) describes a situation in which Susan has a psychological experience. We adopt Experiencer, particularly as in some languages with rich systems of case , there are clear distinctions, central to the grammar, which support a contrast between Patient and Experiencer.

Verbs like know are called stative verbs. Lists of stative verbs in English usually include verbs such as understand, like, believe, see and hear, which denote psychological experiences. Adjectives such as sorry, ashamed and joyful are often included as denoting psychological experiences. The evidence from English, as in (24), is typically in the form of paraphrase relations, such as be visible to X for X sees and be audible to X for X hears.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)