Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Government

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

103-9

2-2-2022

1747

Government

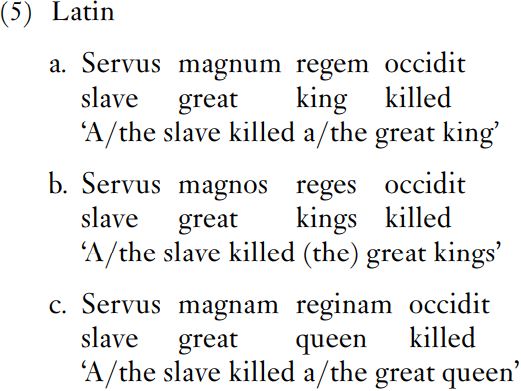

Consider now the examples in (5).

Regem in (5a) is the direct object of occidit and has the suffix -em. The adjective has the suffix -um. In (5b) reges is the direct object of occidit, is plural and has the suffix -es. The adjective has the suffix -os. In (5c), reginam is the direct object of occidit, is singular and has the suffix -am. The adjective has the same suffix. Regem, reginam and reges are said to be in the accusative case. Note that reges, with the same suffix -es, is subject in (2a) and direct object in (5b), but that the adjective has different suffixes.

Occidit is a verb that requires an object in what is called the accusative case. In the examples in (5), occidit, in the traditional formula, governs its object noun in the accusative case; that is, it assigns accusative case to the stems reg- (king) and regin- (queen). Independently of the verb, these nouns are singular in (5a) and (5c) and plural in (5b). The combination of accusative and singular requires the choice of the suffixes -em or -am depending on the stem, and the choice of accusative and plural requires -es for the stem reg-. The properties ‘accusative’ and ‘singular’ or ‘accusative and plural’ are passed on to the adjective in the direct object noun phrase, magn-, and the appropriate suffix is chosen.

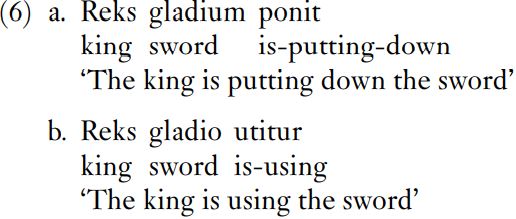

The majority of verbs in Latin assign accusative case to their object noun, but many verbs assign one or other of the remaining three cases. For example, the verb utor (I use) governs its object noun in the ablative case, as shown in (6).

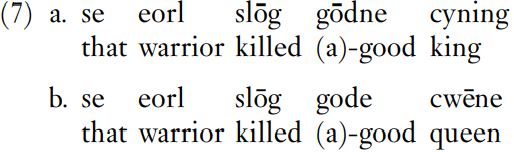

For verb and object noun too, a similar pattern occurs in Old English, as demonstrated in (7).

In (7b), the object noun cwe¯ne, with the suffix -e, is modified by the adjective go¯de, with the suffix -e. This contrasts with the subject noun cwe¯n in (3b) with no suffix and modified by the adjective go¯du, with the suffix -u. In (7a), the noun cyning has no suffix but the adjective does have a special suffix, namely -ne as in go¯dne. There is no contrast in the suffixes added to subject and object plural nouns.

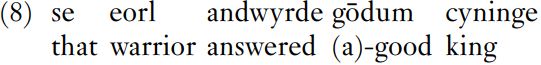

The patterns of suffixes are summed up by saying that slo¯g requires its object noun to be in the accusative case. Other verbs require their noun to be in a different case; andwyrdan ‘answer’, for instance, requires its object noun to take dative suffixes, as shown in (8).

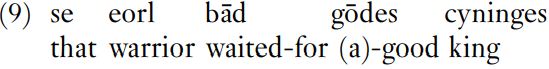

Cyninge in (8) has the dative case suffix -e and go¯dum has the dative suffix -um. The verb bı¯dan ‘wait for’ requires its object noun to take a genitive suffix, as in (9).

In (9), cyninges has the genitive suffix -es and the adjective go¯des has the same suffix.

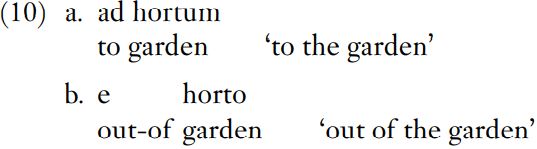

Prepositions in Latin also assign case to their complement nouns. Ad (to) governs nouns in the accusative case, and de (from) governs nouns in the ablative case.

The nominative case was thought of as the case that was used when speakers were using nouns to name entities. The theory was, and indeed still is, that speakers pick out and name an entity and then say something about it. ‘Accusative’ looks as though it should have something to do with accusing; this does not make much sense but results from a mistranslation into Latin of a Greek term meaning ‘what is effected or brought about’. It seems that the central examples of accusative case were taken to be the Classical Greek equivalents of ‘She built a house’.

‘Ablative’ derives from a Latin word meaning ‘taking away’ and occurs with prepositions expressing movement from or off something, as in (10b).

The above Latin examples show that different case-number suffixes are added to nouns and adjectives and that which suffix is chosen in a particular clause depends on the noun. Latin nouns fall into a number of different classes, known as genders.

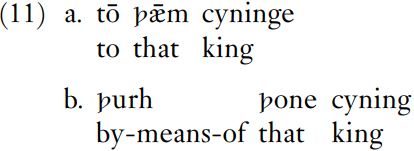

Prepositions in Old English also require their complement nouns to have particular case suffixes. For example, to¯ ‘to’ governs its complement noun in the dative case (like most prepositions), but †urh ‘by means of ’ governs its complement noun in the accusative case. The distinction is exemplified in (11).

In (11a), †æ¯m is the dative form of se ‘that’ and cyninge has the dative suffix -e. In (11b), †one is the accusative form of se but cyning has no suffix.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)