Oblique object and indirect object

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

95-8

الجزء والصفحة:

95-8

2-2-2022

2-2-2022

5191

5191

Oblique object and indirect object

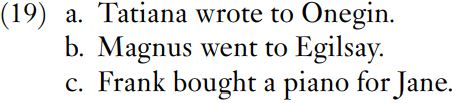

Recent work in syntax deploys the concept of oblique object; in English, any noun phrase that is the complement of a preposition is an oblique object, where the prepositional phrase is itself the complement of a verb. In (19), to Onegin, to Egilsay and for Jane are oblique objects.

Phrases such as to Onegin used to be analyzed as containing indirect object nouns, but this concept of indirect object is problematical. Grammars of English would merely refer to verbs such as TELL, SAY, SHOW and GIVE, which occur in the construction V NP1 TO NP2 or V NP2 NP1: compare Celia gave the car to Ben vs Celia gave Ben the car, where the car is NP1 and Ben is NP2. The indirect object was said to be the noun phrase preceded by to, and the relevant verbs were either listed individually or divided into classes labelled ‘verbs of saying’, ‘verbs of giving’ and so on in order to avoid the label ‘indirect object’ being assigned to phrases such as to Dundee in He went to Dundee.

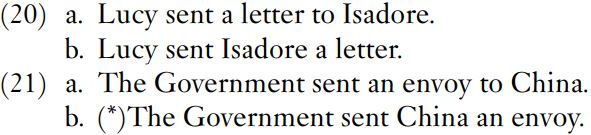

In fact, it is difficult to separate indirect objects from adverbs of direction. It is sometimes suggested that the two can be distinguished on the grounds that indirect object NPs contain animate nouns, whereas adverbs of place contain inanimate nouns denoting countries, towns and other places. If this were correct, we would expect inanimate nouns not to occur immediately to the right of a verb such as sent in (20) and (21).

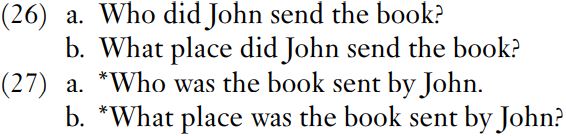

It has been suggested that (21b) is not correct, but the fault is semantic and not syntactic. Example (21b) has the interpretation that a person is sent to China so that China can use him/her as an envoy. This is a rather unusual situation – at least out of context, (21b) seems odd. The oddness can be removed by substituting different lexical items, as in (22).

Example (22) presents China not just as a geographical area but as a body that is to benefit from the engineers. With the appropriate interpretation, then, an inanimate noun can occur to the right of the verb.

Example (22) presents China not just as a geographical area but as a body that is to benefit from the engineers. With the appropriate interpretation, then, an inanimate noun can occur to the right of the verb.

Another suggestion is that indirect objects can occur immediately to the right of the verb but not immediately to the right of genuine adverbs of direction. (Genuine adverbs of direction would not include China in (22).) This suggestion is correct, but it still fails to distinguish indirect objects, because an indirect object noun cannot always occur immediately to the right of the verb, as shown by (23)

The particular examples in (23) have been tested on many classes of students at all levels. Some have accepted some of the examples, especially (23b), but the vast majority have not accepted any of them.

Other evidence that attacks any clear distinction between indirect objects and adverbs of direction is presented in (24)–(25), which illustrate certain syntactic patterns common to indirect objects and adverbs of direction. The first shared property is that both can occur in WH interrogatives with the preposition to at the end or beginning of the clause.

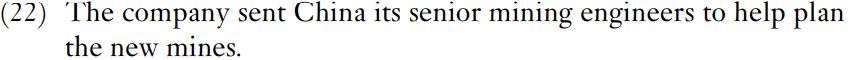

Another property in common is that both can occur in active interrogative WH clauses with to omitted, but not in passive WH interrogatives.

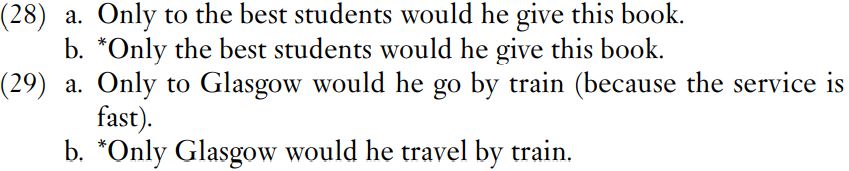

Indirect objects and adverbs of direction can occur at the front of clauses preceded by only. In such constructions, the preposition to cannot be omitted – compare the indirect object in (28) and the adverb of direction in (29).

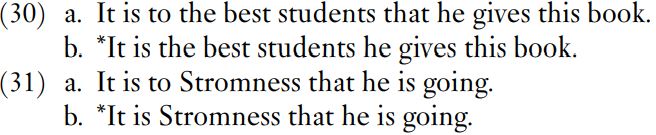

The same applies to the cleft construction in (30) and (31), where the indirect object to the best students in (30) and the adverb of direction to Stromness in (31) are preceded by it is.

The same applies to the cleft construction in (30) and (31), where the indirect object to the best students in (30) and the adverb of direction to Stromness in (31) are preceded by it is.

There is one difference (concealed by the use of what place in (25)): indirect objects are questioned by who … to or to whom, but adverbs of direction are questioned by where. However, this is one difference to be set against a number of similarities, and it could in any case be argued that the difference does not reflect a syntactic category but a difference in the sorts of entities that are the end point of the movement, where being reserved for places, who for human beings.

The analysis indicated by the above data is that we cannot maintain the traditional concept of indirect object as the to phrase with verbs such as give and show and that all verb complements introduced by a preposition should be treated as one category, namely oblique objects.

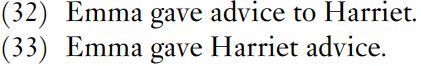

The concept of indirect object is not dead, however. Some traditional analyses applied it to, for example, the phrase to Harriet in (32) and to the phrase Harriet in (33).

The label ‘indirect object’ is useful for Harriet in (33). It can be declared to reflect the fact that while Harriet is an object – compare Harriet was given advice by Emma – it is felt by many analysts to be less of a direct object than advice, even though advice in (33) is not next to the verb.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة