النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Telomeres Have Simple Repeating Sequences

المؤلف:

JOCELYN E. KREBS, ELLIOTT S. GOLDSTEIN and STEPHEN T. KILPATRICK

المصدر:

LEWIN’S GENES XII

الجزء والصفحة:

23-3-2021

2065

Telomeres Have Simple Repeating Sequences

KEY CONCEPTS

- The telomere is required for the stability of the chromosome end.

- A telomere consists of a simple repeat where a G-rich strand at the 3′ terminus typically has a sequence of (T/A)1–4 G>2.

Another essential feature in all chromosomes is the telomere, which “seals” the chromosome ends. We know that the telomere must be a special structure, because chromosome ends generated by breakage are “sticky” and tend to react with other chromosomes, whereas natural ends are stable.

We can apply two criteria in identifying a telomeric sequence:

- It must lie at the end of a chromosome (or, at least at the end of an authentic linear DNA molecule).

- It must confer stability on a linear molecule subjected to multiple rounds of replication and immune from end-joining DNA repair machinery.

The problem of finding a system that offers an assay for function again has been brought to the molecular level by using yeast. All of the plasmids that survive in yeast (by virtue of possessing autonomously replicating sequence [ARS] and CEN elements) are circular DNA molecules. Linear plasmids are unstable (because they are degraded). Could an authentic telomeric DNA sequence confer stability on a linear plasmid? Fragments from yeast DNA that prove to be located at chromosome ends can be identified by such an assay, and a region from the end of a known natural linear DNA molecule—the extrachromosomal ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of Tetrahymena—is able to render a yeast plasmid stable in linear form.

Telomeric sequences have been characterized from a wide range of eukaryotes. The same type of sequence is found in plants and humans, so the construction of the telomere seems to follow a nearly universal principle (Drosophila telomeres are an exception, consisting of terminal arrays of retrotransposons). Each telomere consists of a long series of short, tandemly repeated sequences.

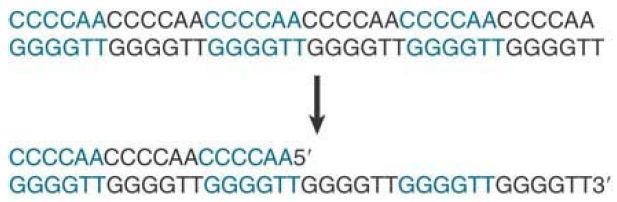

There can be 100 to 1,000 repeats, depending on the organism. Telomeric sequences can be written in the general form 5′- (T/A)nGm-3′ where n is 1 to 4 and m is >1. FIGURE 7.28 shows a generic example. One unusual property of the telomeric sequence is the extension of the G-T–rich strand, which for 14 to 16 bases is usually a single strand. The G-tail is probably generated because there is a specific limited degradation of the C-A–rich strand.

FIGURE 1 A typical telomere has a simple repeating structure with a G-T–rich strand that extends beyond the C-A–rich strand. The G-tail is generated by a limited degradation of the C-A–rich strand.

Some indications about how a telomere functions are given by some unusual properties of the ends of linear DNA molecules. In a trypanosome population, the ends vary in length. When an individual cell clone is followed, the telomere grows longer by 7 to 10 bp (one to two repeats) per generation. Even more revealing is the fate of ciliate telomeres introduced into yeast. After replication in yeast, yeast telomeric repeats are added onto the ends of the Tetrahymena repeats.

Addition of telomeric repeats to the end of the chromosome in every replication cycle could solve the difficulty of replicating linear DNA molecules (discussed in the chapter Extrachromosomal Replicons). The addition of repeats by de novo synthesis would counteract the loss of repeats resulting from failure to replicate up to the end of the chromosome. Extension and shortening would be in dynamic equilibrium.

If telomeres are continually being lengthened (and shortened), their exact sequence might be irrelevant. All that is required is for the end to be recognized as a suitable substrate for addition. This explains how the ciliate telomere functions in yeast.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)