تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Vector areas

المؤلف:

Richard Fitzpatrick

المصدر:

Classical Electromagnetism

الجزء والصفحة:

p 8

13-7-2017

2485

Vector areas

Suppose that we have planar surface of scalar area S. We can define a vector area S whose magnitude is S and whose direction is perpendicular to the plane, in the sense determined by the right-hand grip rule on the rim. This quantity

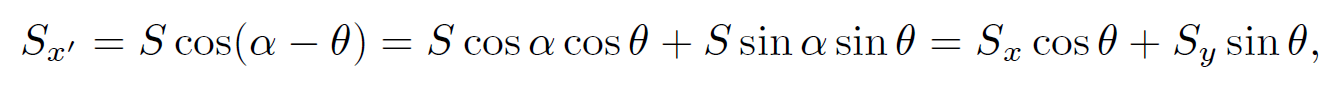

clearly possesses both magnitude and direction. But is it a true vector? We know that if the normal to the surface makes an angle αx with the x-axis then the area seen in the x-direction is S cos αx. This is the x-component of S. Similarly, if the normal makes an angle αy with the y-axis then the area seen in the y-direction is S cos αy. This is the y-component of S. If we limit ourselves to a surface whose normal is perpendicular to the z-direction then αx = π/2 - αy = α. It follows that S = S(cos α, sin α, 0). If we rotate the basis about the z-axis by θ degrees, which is equivalent to rotating the normal to the surface about the z-axis by –θ degrees, then

(1.1)

(1.1)

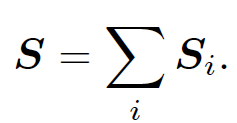

which is the correct transformation rule for the x-component of a vector. The other components transform correctly as well. This proves that a vector area is a true vector. According to the vector addition theorem the projected area of two plane surfaces, joined together at a line, in the x direction (say) is the x-component of the sum of the vector areas. Likewise, for many joined up plane areas the projected area in the x-direction, which is the same as the projected area of the rim in the x-direction, is the x-component of the resultant of all the vector areas:

(1.2)

(1.2)

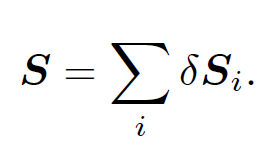

If we approach a limit, by letting the number of plane facets increase and their area reduce, then we obtain a continuous surface denoted by the resultant vector area:

(1.3)

(1.3)

It is clear that the projected area of the rim in the x-direction is just Sx. Note that the rim of the surface determines the vector area rather than the nature of the surface. So, two different surfaces sharing the same rim both possess the same vector areas. In conclusion, a loop (not all in one plane) has a vector area S which is the resultant of the vector areas of any surface ending on the loop. The components of S are the projected areas of the loop in the directions of the basis vectors. As a corollary, a closed surface has S = 0 since it does not possess a rim.