Graphs :Visiting Vertices

المؤلف:

W.D. Wallis

المؤلف:

W.D. Wallis

المصدر:

Mathematics in the Real World

المصدر:

Mathematics in the Real World

الجزء والصفحة:

99-100

الجزء والصفحة:

99-100

9-2-2016

9-2-2016

1966

1966

Again, let us consider graphs used to model networks of roads. In the preceding chapter, we looked at efficient ways to examine the edges of a graph—the sort of work that a highway inspector or snow plow driver might do. Now let us consider the vertices. For example, a traveling salesman might want an efficient route to visit all the cities in an area. He would not care whether all the roads were traversed. So he is concerned with vertices, not edges.

Some Classes of Graphs

In this chapter we will only be concerned with simple graphs; there will be no loops or multiple edges.

When discussing Euler walks and circuits, there was no restriction on the vertices; one could pass through a vertex as many times as necessary. We are now going to limit ourselves to visiting vertices once, so we need some more definitions.

We shall define a path (A,B,C,...,Y,Z) to be a walk (A,B,C,...,Y,Z) in which there are no repeated vertex. If (A,B,C,...,Y,Z) is a path of length at least 2 and there is also an edge ZA then the configuration consisting of the path together with the edge ZA is called a cycle. So a cycle is a circuit with no repeated edges.

Paths and cycles can both be considered as graphs in their own right. We define the path Pn to be a graph with n vertices and n − 1 edges that constitute a path of length n−1. For example, if the vertices are X1,X2,...,Xn, the edges might be X1X2, X2X3, ..., Xn−1Xn. Similarly, the cycle Cn is a graph whose n vertices and n edges form a cycle of length n: typically, the vertices may be X1,X2,...,Xn, and the edges are X1X2,X2X3,...,Xn−1Xn,XnX1. In a cycle, every vertex has degree 2.

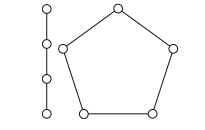

Figure 1.1 shows copies of P4 and C5.

We have already seen complete graphs; remember that Kn is a graph with n vertices in which every pair of vertices is joined by an edge. Another interesting

Fig. 1.1 A path and a cycle

graph is the complete bipartite graph Km,n. This graph has two sets of vertices, one of size m and one of size n, and two vertices are joined by an edge if and only if they are in different sets.

Another type of graph that will be important is a tree. This is a connected graph that contains no cycles. The tree diagrams we saw in (Probability) are in fact trees; and we shall see more of them in a later chapter.

By a subgraph we mean a collection of the vertices and edges in a graph that by themselves constitute a graph. If an edge XY is included in the set of edges of a subgraph, then both vertex X and vertex Y will necessarily be in its set of vertices; however, if X and Y are vertices in a subgraph, then it is possible that XY is not an edge in the subgraph, even if XY was an edge in the original graph.

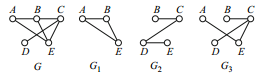

Figure 1.2 shows a graph G and three of its subgraphs: a cycle G1 (a copy of C3), a path G2 (a copy of P4), and another subgraph G3, which is a tree. Note that the cycle G1 could be denoted (A,B,E), (B,E,A), (E,A,B), (A,E,B), (E,B,A) or (B,A,E); a cycle has no intrinsic start or finish point, and a copy ofCn can be written (as a list of vertices) in 2n ways. On the other hand, to specify a path, you must start at one of its endpoints; G2 can be written either as (B,C,D,E) or as (E,D,C,B).

Fig. 1.2 Examples of subgraphs

Sample Problem 1.1 In the graph G of Fig. 1.2, list all the paths that start with edge AE.

Solution. (AE) is itself a path, of length 1. After A,E one could go on to B, giving the paths (A,E,B), (A,E,B,C), (A,E,B,C,D), or to C, giving (A,E,C), (A,E,C,B), (A,E,C,D).

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية البيان

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية البيان

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة