Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Assumptions

المؤلف:

Bernd Heine and Tania Kuteva

المصدر:

The Genesis of Grammar

الجزء والصفحة:

P14-C1

2026-02-19

50

Assumptions

We saw above that there are quite a number of problems, which are due mainly to the fact that language genesis and evolution are not immediately accessible to empirical analysis, and that any attempt at accessing them involves some ‘‘poking in the dark.’’ Perhaps the main problem facing research on language genesis and development is methodological: What kind of method and evidence is required to produce a plausible hypothesis on language genesis and/or evolution (see Botha 2003a)?

Bickerton (2005) asserts that language evolution is an interdisciplinary Weld and that ‘‘it is at best incautious to frame hypotheses on the basis of evidence from a single discipline.’’ While we are fully aware of the potential offered by interdisciplinary work and the integrating approaches sketched in “Previous work”, especially considering the complex subject matter at stake, Bickerton’s position is not the one taken here. Rather, we believe that much more disciplinary research is required before it is possible to construct a viable overall theory of language evolution. Quite a number of hypotheses that are on the market have been based on interdisciplinary research—but many of them are of what in evolutionary psychology and biology tends to be referred to as the ‘‘just-so story’’ type (Eldredge 1995). That is to say, they are hypotheses that lack the ability to be testable at least in principle on the basis of empirical evidence as it can be obtained from research provided by individual disciplines—Bickerton’s (1990, 2005) own hypothesis being a case in point. Indeed, hypotheses based on evidence and the methodology of a single discipline are severely limited in scope; but they do at least allow some particular phenomenon to be considered in a consistent way, without having to rely on more or less conjectural reasoning across disciplines.

The goal is a modest one. By using one specific method of linguistic reconstruction, namely that of grammaticalization theory, we aim to find answers to at least some of the questions listed in (1) (see “Looking for answers”). This methodology is based on the following observations:

(2) Observations

a. The development from early language to the modern languages is about linguistic change. Accordingly, in order to reconstruct it we need to know what is a possible linguistic change and what is not.

b. An important driving force of linguistic change is creativity.

c. Linguistic forms and structures have not necessarily been designed for the functions they presently serve.

d. Context is an important factor determining grammatical change.1

e. Grammatical change is directional.

Much of the past and present work on the genesis of grammar relies on generalizations on synchronic language structure and does not take into account findings on how languages change, in particular which changes are possible ones and which are not. There is no indication that the principles of language change in early language were significantly different from the ones we observe in modern languages; hence, in accordance with (2a) we assume that early language can be studied on the basis of the same principles as modern languages. Conversely, a hypothesis on language evolution that is not in accordance with observations on change in modern languages is less plausible than one that is; we will return to this issue in “The present approach”.

Linguistic change may be viewed on the one hand as leading from one type of language to another, for example (with reference to some discussions that have been led on language evolution) from non-syntactic to syntactic language. On the other hand, it is taken to refer to a modification of individual properties or structures of languages. Our concern is with the latter kind of change; however, given that there is an appropriate number or cluster of modifications of individual properties in some language or group of languages, it is possible to phrase such modifications in terms of linguistic change leading from one type of language to another.

A considerable portion of the recent literature on grammatical change highlights activities relating to language acquisition by children, learning, parsing, productivity, etc. While such work captures important aspects of linguistic behavior, it tends to underrate the significance of a factor that we consider to be central to many kinds of grammatical change, namely creativity, and (2b) constitutes a cornerstone of the methodology used in the present work. Creativity, as we understand it here, must not be confused with productivity, that is, with the use of a limited set of taxa and rules to produce a theoretically unlimited number of taxonomic combinations or structures. Rather than with conforming with rules or constraints, creativity in this sense is about modifying rules or constraints by using and combining the existing means in novel ways, proposing new meanings and structures. The perspective adopted is therefore of a different kind than that underlying the approaches alluded to above, and so is the methodology that will be used and, consequently, so also are the linguistic data that we will draw on when looking for answers to the questions in (1).

In a nutshell, the main thesis here is that the emergence and development of human language is the result of a strategy whereby means that are readily available are used for novel purposes. Conceivably, this strategy is not an innovation of Homo sapiens, a manifestation of it might be seen, for example, in the tool-making abilities of some non-human primates. What is new, however, is that the strategy has been further developed, increasingly refined, and extended to a new domain of human behavior, namely linguistic communication.

Our concern here is less with the current utility of words or constructions but rather with what these entities have been designed for. Statement (2c) concerns an issue that has received considerable attention in evolutionary biology: Do categories serve the purpose for which they were designed? Answering this question is faced with the problem that there is not always agreement among scholars on how the functions of a given category are to be defined. However, there are some data that suggest an answer. To begin with, there is the general observation made independently in a number of studies that language change is a by-product of communicative intentions not aimed at changing language (see especially Keller 1994; Haspelmath 1999a). In fact, when a new functional category is created, there is nothing to suggest that this is what the speakers who are involved in this process really intend to happen.

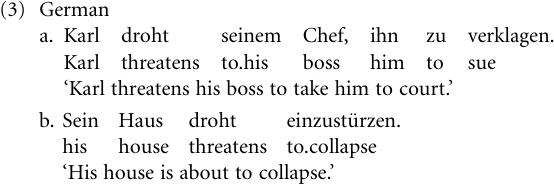

The following example, which is characteristic of the way new auxiliaries for tense, aspect, or modality arise (see "The fourth layer: demonstratives, adpositions, aspects, and negation"), may illustrate this (Heine and Miyashita 2006). In German, the item drohen ‘to threaten’ occurs both as a lexical verb, cf. (3a), and as an auxiliary having the syntax of a raising verb but the aspectual-modal meaning ‘something undesirable is about to happen’ (3b).

Historical records show that (3a) represents the earlier situation, attested in Old and Middle High German, while (3b) is a later development of (3a) arising in Early New High German after 1700. But at no stage in the process from lexical verb to auxiliary can speakers of German be assumed to have intended to ‘‘design’’ a functional category or else a new auxiliary construction. The process started in the first half of the sixteenth century when instead of human agents, abstract nouns such as Sünde ‘sin’, Urteil ‘verdict’, Gesetz ‘law’, or Tod ‘death’ could be used productively as subject referents— in other words, when the use of the action verb drohen was extended metaphorically to inanimate concepts conceived as threatening agents. Subsequently, the use of the verb within animate subjects was generalized, where the lexical meaning ‘someone acting intentionally’ made no more sense. Consequently, the verb was desemanticized in such contexts and the aspect ual-modal meaning surfaced. This triggered a number of decategorialization processes,2 in that the erstwhile lexical verb lost most of its verbal properties, such as the ability to take auxiliaries or to control its subject—with the effect that by the mid-eighteenth century there evolved a functional category of the kind exemplified in (3b). In sum, the current utility of the auxiliary does not reflect the purpose for which it was designed, which was simply to treat threatening forces metaphorically like human agents.

Another, much discussed example concerns the French negation marker pas. In a sentence such as Je (ne) sais pas (I (NEG) know NEG) ‘I don’t know’ it is a negation marker, but this is not what it used to be, or what it was designed for: pas was a noun meaning ‘step’ which was introduced as a device not specifically for negation but rather for effciently supporting a negative predication3 (cf. He didn’t move a step), and it is only with the gradual decline of the erstwhile negation marker ne that pas assumed its present-day function as the primary or the only marker of negation. To conclude, the French negation marker serves a function that it was not designed for by earlier speakers of French. Once again, the original function—that of reinforcing another word—has little in common with the current utility of the item concerned. Even if one were to assume that there are cases where the product of grammatical change is exactly what the speakers concerned had intended to achieve, there are other cases showing that functional categories may change in such a way that they bear little resemblance to their original design. A paradigm case is provided by the grammaticalization of demonstratives as described by Greenberg (1978): The first step in this process is from demonstrative to definite article; subsequently the element may develop further to be used for indefinite reference, and in a final stage the erstwhile demonstrative may turn into a semantically (largely empty) marker of nominalization. To conclude, the evidence available suggests that the current utility of functional categories need not have anything to do with the motivations that speakers had when they ‘‘designed’’ them.

The example of the French negation marker pas alluded to above also illustrates (2d): It shows that it may be, and frequently is, the contextual or co-textual environment—in short, the context—which determines semantic and syntactic change: There is nothing in the meaning of the French noun pas ‘step’ that would suggest the meaning of negation. It was the use of this noun in one particular context that shaped the development from noun to ‘‘emphasizer’’ and finally to negation marker; otherwise, pas has remained until today what it used to be, namely a noun for ‘step’. Another example to illustrate (2d) is the following. In many languages there is a grammatical distinction between an indicative and a subjunctive mood. While these two categories express contrasting meanings, it may happen that there is a change from indicative to subjunctive mood. The way this happens can be described as follows: In many languages there is a progressive aspect category expressing ongoing processes. Now, progressives tend to spread to contexts where they denote present tense and habitual events, eventually ousting an already existing present indicative tense construction in main clauses. But this old present tense construction can survive in subordinate clauses, and since subordinate clauses tend to be associated with subjunctive functions, the old construction can become a canonical marker of a new subjunctive mood. Languages that have been reported to have undergone a development along these lines include Modern Armenian, Tsakonian Greek, Modern Indic, Persian, and Cairene Arabic (Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994: 230–6; Haspelmath 1998b: 41–5; Croft 2000: 127–8). This kind of change, which may also lead from present to future tense constructions, is not motivated by semantic or syntactic forces but rather by the pragmatic factor of context extension (see “Extension”).4

Statement (2e) is a cornerstone of grammaticalization theory, which underlies the present work. For example, as we saw above, lexical verbs commonly develop into auxiliaries for tense, aspect, or modality, while it is unlikely that a tense auxiliary develops into a lexical verb. Similarly, demonstratives give rise to definite articles, and numerals for ‘one’ to indefinite articles, or body part nouns may give rise to adpositions (prepositions or postpositions), while it is unlikely that articles develop into demonstratives, adpositions into nouns, or auxiliaries into lexical verbs (but see “Problems”).

1 This concerns both the linguistic and the extra-linguistic context.

2 Concerning the terms desemanticization and decategorialization, “Methodology”.

3 In the wording of an anonymous referee of an earlier version, ‘‘the grammaticalization of Old French negation markers like pas < lat. passu(m) ‘step’, mie < lat. mica(m) ‘crumb’, point < lat. punctu(m) ‘point’ etc. started when they were used in context of scalar argumentation (‘I will not move a step’, ‘I will not eat a crumb’, ‘I cannot even see a point’, etc.). Here, they already serve the purpose of efficiently denying/negating’’.

4 As pointed out by an anonymous referee of an earlier version, this example concerns creativity and innovation only in a very indirect fashion.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)