Comparing the generative view of language acquisition

In this section, we compare the usage-based account of language acquisition with the nativist view that is assumed within the generative framework developed by Chomsky. This comparison is important because, in many respects, the usage-based view and the nativist view stand in direct opposition to one another. Furthermore, Chomsky’s ideas were influential among developmental psycholinguists, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, and are sometimes presented as the ‘standard’ view of language acquisition in many contemporary linguistics textbooks. More recently, cognitive theories of child language acquisition have been developed partly in response to Chomsky’s claims. We look in more detail at the nativist hypothesis and the linguistic modularity hypothesis, and at the cognitive response to these hypotheses. We then look at alternative interpretations of empirical findings in language acquisition and, finally, consider localisation of linguistic function in the brain.

The nativist hypothesis

Until the 1960s, the main influence on developmental psychology was the theory of behaviourism. This is the doctrine that learning is governed by inductive reasoning based on patterns of association. Perhaps the most famous example of associative learning is the case of Pavlov’s dog. In this experiment a dog was trained to associate food with a ringing bell. After repeated association, the dog would salivate upon hearing the bell. This provided evidence, the behaviourists argued, that learning is a type of stimulus–response behaviour. The behaviourist psychologist B. F. Skinner (1904–90), in his 1957 book Verbal Behavior, outlined the behaviourist theory of language acquisition. This view held that children learnt language by imitation and that language also has the status of stimulus–response behaviour conditioned by positive reinforcement.

In his famous 1959 review of Skinner’s book, Chomsky argued, very persuasively, that some aspects of language were too abstract to be learned through associative patterns of the kind proposed by Skinner. In particular, Chomsky presented his famous argument, known as the poverty of the stimulus argument, that language was too complex to be acquired from the impoverished input or stimulus to which children are exposed. He pointed out that the behaviourist theory (which assumes that learning is based on imitation) failed to explain how children produce utterances that they have never heard before, as well as utterances that contain errors that are not present in the language of their adult caregivers. Furthermore, Chomsky argued, children do not produce certain errors that we might expect them to produce if the process of language acquisition were not rule-governed. Chomsky’s theory was the first mentalist or cognitive theory of human language, in the sense that it attempted to explore the psychological representation of language and to integrate explanations of human language with theories of human mind and cognition. The poverty of the stimulus argument led Chomsky to posit that there must be a biologically predetermined ability to acquire language which, as we have seen, later came to be called Universal Grammar.

Tomasello (1995) argues that there are a number of significant problems with this hypothesis. Firstly, Tomasello argues that Chomsky’s argument for a Universal Grammar, which was based on his argument from poverty of the stimulus, took the form of a logical ‘proof’. In other words, it stemmed from logical reasoning rather than from empirical investigation. Furthermore, Tomasello argues, the poverty of the stimulus argument overlooks aspects of the input children are exposed to that would restrict the kinds of mistakes children might ‘logically’ make.

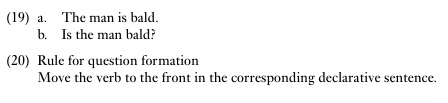

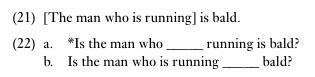

For instance, if children were employing the associative or inductive learning strategies proposed by the behaviourists then, as Chomsky pointed out, we might expect them to make mistakes in question formation. For example, based on data like the sentences in (19), children might posit the rule in (20) as part of the inductive process.

Furthermore, given the data in (21), we might expect children to produce sentences like (22a), which is formed by moving a verb to the front of the sentence. The underscore shows the position of the verb in the corresponding declarative sentence. However, as Chomsky pointed out, children do not make errors like these, despite the absence of any direct evidence that such constructions are not well-formed, and despite the fact that constructions like (22b) are rather rare in ‘motherese’ or child-directed speech. Despite this, children produce examples like (22b), which rests upon the unconscious knowledge that the first is in (21) is ‘buried’ inside a phrasal unit (bracketed).

According to Chomsky, children must have some innate knowledge that prohibits sentences like (22a) but permits sentences like (22b). According to Tomasello, the problem with this argument is that, in the input children are exposed to, they do not hear the relative pronoun who followed by an -ing form. In other words, they do have the evidence upon which to make the ‘right’ decision, and this can be done by means of pattern-finding skills.

Tomasello’s second argument relates to the nature of the learning skills and abilities children bring with them to the learning process. It has now been established beyond dispute that children bring much more to this task than the inductive learning strategies posited by the behaviourists, which Chomsky demonstrated in 1959 to be woefully inadequate for the task of language acquisition. In the intervening years, research in cognitive science has revealed that infants bring with them an array of cognitive skills, including categorisation and pattern-finding skills, which emerge developmentally and are in place from at least seven months of age. In addition, children also develop an array of sociocognitive (intention-reading) skills, which emerge before the infant’s first birthday. On the basis of these facts, there is now a real alternative to the nativist hypothesis.

The third argument that Tomasello raises relates to the notion of language universals. In the 1980s Chomsky proposed a theory of Universal Grammar called the Principles and Parameters approach. According to this approach, knowledge of language consists of a set of universal principles, together with a limited set of parameters of variation, which can be set in language-specific ways based on the input received. From this perspective, linguistic differences emerge from parameter setting, while the underlying architecture of all languages is fundamentally similar.

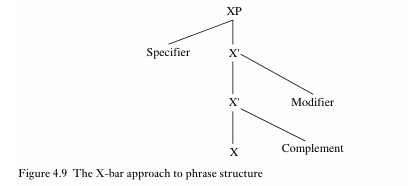

For example, one linguistic universal in the principles and parameters model is the X-bar schema. This is a small set of category neutral rules that is argued to underlie the phrase structure of the world’s languages. This idea is illustrated in Figure 4.9. In this diagram, X is a variable that can be instantiated by a word of any class, and P stands for phrase. X represents the head of the phrase, which projects the ‘identity’ of the phrase. The specifier contains unique elements that occur at one of the ‘edges’ of the phrase, and the complement is another phrasal unit that completes the meaning of the head. Amodifieradds additional optional information. The name ‘X-bar’ relates to the levels between head (X) and phrase (XP), which are labelled X to show that they have the same categorial status (word class) as X, but are somewhere between word and phrase.

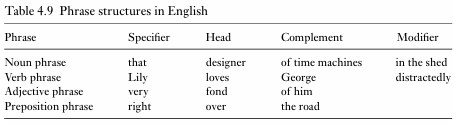

Table 4.9 provides some examples of phrase structures in English that could be built out of this basic structure.

Notice that some of the cells in Table 4.9 are empty. The idea behind the X-bar model is that only the head is obligatory in the phrase, although each individual head may bring with it some requirements of its own for which this structure can be exploited. For example, a transitive verb will require a com plement (object), while an intransitive verb will not. Another important feature of this model is that while hierarchical relations between head, specifier, com plement and modifier are universal (this means that the phrasal unit underlies the phrase structure of every language), linear relations are not (this means that the parts can occur in different linear orders). This is where the idea of para meter setting comes in. A child exposed to a head initial language like English adopts an X-bar structure where the head X precedes the complement. A child exposed to a head final language like Korean adopts an X-bar structure where the head follows its complement. Because the X-bar model specifies that the complement always occurs next to the head, only two ‘options’ are permitted. This illustrates the restricted nature of the parameters of variation in this model.

Tomasello argues, as have many opponents of the generative approach, that the X-bar model does not account for non-configurational languages like the native Australian language Dyirbal. A non-configurational language is one in which words are not grouped into obvious phrasal units. The application of X-bar theory to this type of language raises a number of questions about how the Dyirbal child sets his or her head initial/final parameter. Cognitive lin guists like Tomasello argue, then, that the ‘universals’ posited by generative linguists arise from theory-internal considerations rather than appropriately reflecting the diversity and complexity of language.

The linguistic modularity hypothesis

As we have seen, the generative model rests on the hypothesis that there is a specialised and innate cognitive subsystem or ‘language faculty’: an encapsulated system of specialised knowledge that equips the child for the acquisition of language and gives rise to unconscious knowledge of language or competence of the native speaker. This system is often described as a module (see Chomsky 1986: 13, 150; Fodor 1983, 2000). Patterns of selective impairment, particularly when these illustrate double dissociation, are often thought by generative linguists to represent evidence for the encapsulation of such cognitive subsystems. Examples of selective impairment that are frequently cited in relation to the issue of the modularity of language are Williams Syndrome, linguistic savants and Specific Language Impairment. Williams Syndrome is a genetic developmental disorder characterised by a low IQ and severe learning difficulties. Despite this, children with this disorder develop normal or super normal language skills, characterised by particularly fluent speech and a large and precocious vocabulary. Linguistic savants are individuals who, despite severe learning difficulties, have a normal or supernormal aptitude for language learning. In the case of Specific Language Impairment, a developmental dis order that is probably genetic, individuals perform normally in terms of IQ and learning abilities, but fail to acquire language normally, particularly the grammatical aspects of language. These patterns of impairment constitute a case of double dissociation in the sense that they can be interpreted as evidence that the development of language is not dependent upon general cognitive development and vice versa. This kind of evidence is cited by some generative linguists in support of the modularity hypothesis (see Pinker 1994 for an overview).

Interpretations of empirical findings in child language acquisition When looking at empirical evidence for or against a particular theory of language, it is important to be aware that the same set of empirical findings has the potential to be interpreted in support of two or more opposing theories at the same time. In other words, while the empirical findings themselves may be indisputable (depending on how well-designed the study is), the interpretation of those findings is rarely indisputable. For example, while Tomasello argues that the one-word and two-word stages in child language provide evidence for item-based learning, generative linguists argue that the existence of these states provides evidence for a ‘predetermined path’ of language development, and that furthermore the order of units within the two-word expressions provides evidence for the underlying rule-based system that emerges fully later. Moreover, while Tomasello argues that the tendency for infants to attend to familiar linguistic stimuli provides evidence for pattern finding ability, generative linguists argue that this provides evidence for the existence of a universal ‘pool’ of speech sounds that the child is equipped to distinguish between, and that parameter setting abilities are evident in the infant. As this brief discussion illustrates, the developmental psycholinguistics literature is fraught with such disputes and represents an extremely complex discipline. The interpretation of such findings should always be approached critically.

Localisation of function in the brain The final issue we consider here is the localisation of linguistic function in the brain. So far, we have been discussing models of mind rather than brain. Of course, unlike the mind, the brain is a physical object, and neuroscientists have been able to discover much in recent years about what kinds of processes take place in different parts of the brain. In fact, we have known since the nineteenth century that there are parts of the brain that are specialised for linguistic processing, for most if not all people. There is an overwhelming tendency for language processing to take place in the left hemisphere of the brain, and areas responsible for the production of language (Broca’s area) and comprehensionof language (Wernicke’s area) have been shown to occupy dis tinct parts of the brain. These findings have prompted many linguists to argue that this supports the view that we are biologically predetermined for language. However, this is not an issue about which cognitive linguists and generative linguists disagree. The nature of their disagreement concerns the nature of these biological systems: whether they are domain-general or specialised. The facts concerning localisation of function do not provide evidence for or against either the cognitive or the generative view, given that both are models of mind.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة