Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The distribution of degree expressions - The degree expression continuum

المؤلف:

JENNY DOETJES

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P124-C6

2025-04-19

594

The distribution of degree expressions - The degree expression continuum

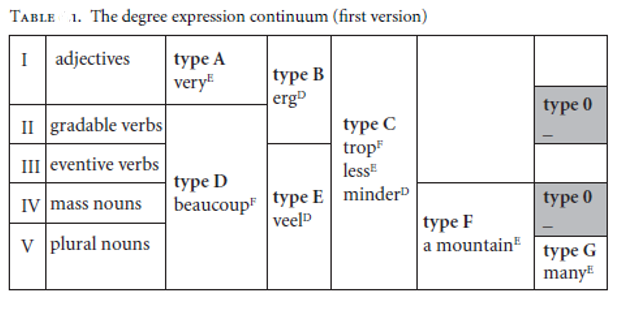

The data discussed so far give a rather simple view of the distributions of degree expressions. According to the examples in (1), they are either compatible with different categories or they are compatible with adjectives only. It turns out that the distributional patterns are far more complex when we start looking outside of the adjectival system. This section will give further insight into these patterns, on the basis of which I will claim that the distributions of degree expressions forma continuum. A rough first version of this continuum, based on the examples in (1), is given in Table 1.

It seems to be the case – and this view will be motivated on the basis of a large number of examples below – that degree expressions do not cover several non-adjacent fields of the continuum in Table 1. That means, for instance, that an expression of type 0, found with gradable verbs and with mass nouns but nothing else (see the gray-coloured cells in Table 1) is predicted to not exist.

Table 1 only contains the types of expressions given in (1). It will turn out later in this section that the classification in the table is incomplete. For instance, adjectives may be used as eventive predicates. In that case they fall in class III. Also, the table does not include comparatives, while these can be modified by a degree expression (e.g. much bigger). Comparatives combine with type D and type E expressions rather than type A or B (beaucoup/∗très plus F / veel/∗erg meerD ‘much/∗very more’), which suggests that they are situated somewhere near the gradable verbs.1 In the remainder of this section I will give examples of the different types that are given in Table 6.1, mainly in English (E), Dutch (D), and French (F).

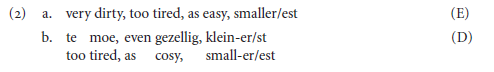

Type A modifiers are typically adjectival modifiers. There are some clear cases of these modifiers in English and Dutch. The properties of French type A look-alikes, and more specifically those of très. In addition to modifiers such as very and as, type A also includes comparative and superlative morphemes, as these usually combine with adjectives only.2 Quite generally it seems to be the case that morphological comparatives and superlatives combine with adjectives, while analytic comparatives tend to have a larger distribution (cf. -er versus more in English).

The interpretations that we find for type A modifiers are equal degree (as, even), excessive degree (too, te), comparative (-er), superlative (-(e)st), high degree (very).

Obviously, it is not the case that all adjectives allow for the use of modification by one of these modifiers. As noted by Bolinger (1972), among many others, it is by no means true that all adjectives are intensifiable. As expected, the unintensifiable ones are incompatible with type A expressions. Moreover, Kennedy and McNally (2005) argue that the possibility of using very depends on the presence of a relative standard. I will get back to the role of the relative standard and of scalar properties of adjectives at various points below.

At first sight type A expressions are compatible with PPs as well, as in very in love. However, the possibility of using these PPs in typically adjectival positions (3a) suggests that they should be considered to be adjectives “in disguise,” on a par with collocations such as forget-me-not, which behaves syntactically as a noun rather than a verb phrase (see Neeleman et al. 2004).

Type B expressions are usually interpreted as intensifiers and, according to the data discussed so far, they are compatible with adjectives and gradable verbs. Some examples are given in (4):

The typical meaning of these expressions is either extreme degree or high degree. In this respect, this class is more restricted than type A. The source of these expressions is usually an adverb that has inherently a (very) high degree meaning, such as horribly. The lexical interpretation of these adverbs seems to fade away, resulting in an extreme degree or high degree modifier. The Dutch word erg originally meant serious, as in een erge ziekte ‘a serious illness.’ In some contexts only the high degree interpretation is left, as illustrated by erg gelukkig ‘very happy.’ In many cases a slight connotation remains that usually reflects the original meaning of the word. French atrocement ‘cruelly, brutally’ can be used nowadays in expressions such as des murs atrocement blancs ‘extremely white walls,’ but the use of atrocement still introduces a negative connotation. On the other hand, there are cases such as Dutch geweldig, which is derived from the word geweld ‘violence,’ but nonetheless has a positive connotation in modern Dutch.

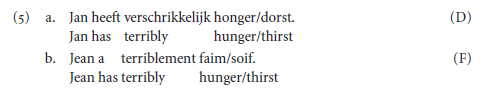

The expressions of this type may also be used to modify predicative nouns, such as honger/faim ‘hunger’ and dorst/soif ‘thirst’ in the Dutch and French examples in (5).3

Type C expressions are the first type discussed here that can be used both as intensifiers and as expressions indicating a degree of quantity. The degree of quantity interpretation occurs with nouns and eventive verbs. For instance, when these expressions are combined with a plural noun such as books, they indicate the degree of quantity of books. In combination with an eventive verb, the degree expression indicates the degree of quantity corresponding to the event (see Bach 1986 and Krifka 1986 for arguments in favor of representing nominal and verbal quantity in a similar way). Degree expressions typically combine with plural and mass terms, which both have cumulative reference.

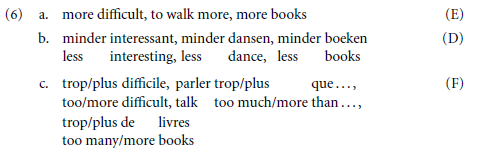

Type C includes French trop as well as English more and less, all of which combine with adjectives, verbs and nouns alike (cf. 1):

The different interpretations obtained in these three contexts can be illustrated on the basis of the examples in (6a). More in more difficult indicates that the intensity of the difficulty exceeds a certain point, while more in to walk more and more books indicates that the degree of quantity corresponding to walking and books respectively exceeds a certain amount or quantity.

Even though type C is not widespread in English and Dutch, where it is mostly restricted to more, less, and enough, Romance languages manifest a large variety of type C expressions, including the counterpart of several type A expressions in English. Examples include Portuguese muito‘very, much/many’ and Spanish demasiado ‘too (much/many).’ Consider for instance the examples in (7):

The typical meanings of type C expressions are the same as the typical meanings of type A: comparative (non-morphological), superlative (nonmorphological), excessive degree (French trop ‘too (much)’), high degree (Portuguese muito ‘very, much’).4

Note that the comparative more in English is exceptional in the sense that it cannot combine with all scalar adjectives. Its use with adjectives is phonologically restricted. The use of the comparative suffix -er is restricted to adjectives of at most two syllables, while more combines with other adjectives and also with nouns and verbs (see Di Sciullo and Williams 1987 for an account of this in terms of blocking).

In general, type C expressions combine with plurals and with mass nouns alike. There are some cases of type C expressions that do not combine with plural nouns, however. The class of small amount expressions such as a bit in English, een beetje in Dutch, and un peu in French systematically resist the use with a plural noun. Interestingly, there do not seem to be expressions that combine with plurals, with verbs and/or adjectives, and that are incompatible with mass nouns.

Type D expressions are similar to type C expressions. However, even though they can be interpreted as “intensifiers” this use is not freely available in combination with adjectives, and is usually restricted to abstract verbs. Examples are English a lot and French beaucoup, as well as autant ‘as much’ and tant ‘so much.’ In Dutch there are no clear cases of this type.

Again we may observe that the meanings we find are fairly similar to the ones we have found for types A and C.

An interesting member of this class is English much.5 Kennedy and McNally (2005) discuss the distribution of English much in the adjectival domain. They argue that much is compatible with those adjectives that introduce a lower closed scale, but not with others. This is illustrated by the contrast in (9). The adjective tall in a tall man indicates that the man is taller than an expected value (the relative standard), rather than a zero value on a scale of tallness. As a result, not tall does not imply a zero level on the scale of length. However, in the case of appreciated, we are dealing with a lower closed scale, which means that not appreciated corresponds to a lack of appreciation.

Type E is not very common. Unlike type D, this type is incompatible with gradable non-eventive verbs. If combined with a verb, it can only indicate a degree of quantity, and therefore the verb has to denote an activity or a plural event (see the discussion on type C above). The difference between what I call here type D and type E was first observed by Obenauer (1984) for French beaucoup (type D) and German viel (type E). Dutch veel is similar to German viel in this respect. Contrary to their French and English counterparts in (8), veel and viel cannot be used to modify gradable non-eventive verbs.

The typical meaning of expressions of this type is one of high degree. Their existence in Dutch and German seems to be related to the existence of a neutral high degree expression of type B. Dutch erg and German sehr are used with adjectives and gradable verbs, and have a neutral high degree meaning as illustrated in (11).

It seems that the type B neutral high degree expression erg blocks the use of veel in this context (see Doetjes 1997 for an account in terms of the Elsewhere Condition). As a result, the only meaning type that exists for this type is one of neutral high degree.

Interestingly, comparative adjectives are modified by veel rather than by erg in Dutch:

This suggests that comparatives pattern with eventive verbs rather than with adjectives and/or gradable verbs.

It is interesting to compare the use of comparatives in combination with degree modifiers to their use with measure phrases such as two meters. It turns out that degree modification is not completely parallel to modification by a measure phrase. Consider for instance the case of tall, which may be modified by measure phrases indicating length (e.g., two meters tall). The same type of measure can be used with the comparative form of the adjective, as in two centimeters taller. In the case of degree words, the positive and the comparative do not behave alike, as shown by the pairs very tall (type A)/much taller (type C/D) and erg groot (type B)/veel groter (type E). Kennedy and McNally (2005) analyze the difference between much and very in these examples in terms of presence versus absence of a lower closed scale. The comparative adjective taller introduces a lower closed scale, while the adjective tall does not (cf. the contrast between 9a and 9b). This cannot explain the Dutch facts, however. Erg is compatible with adjectives such as gewaardeerd, which are argued to introduce a lower bound and as such require the use of much in English (cf. 9b). Thus the use of veel rather than erg in veel groter has to be explained in a different way.

The difference between degree modifiers and measure phrases can be further illustrated by the French facts in (13). In French, degree modifiers of the relevant type (not A or B) may modify the comparative directly, while measure phrases introduce a different syntax:

I will not further discuss the issue of measure phrases here. As for degree modification, the facts discussed above indicate that the comparative patterns with eventive verbs.

A final context where we find type E expressions rather than type A or B expressions is that of predicative eventive adjectives. Consider the contrast between veel ziek and erg ziek in (14).

In (14a) the global amount of the event of being ill is modified, while (14b) indicates that Jan is seriously ill. Similarly, in French beaucoup malade corresponds to veel ziek/ill a lot, while très malade corresponds to erg ziek/very ill. In the final version of the degree expression continuum presented at the end of this section, comparatives and eventive adjectives will be classified along with eventive verbs.

Type F expressions are found with nouns only. They are compatible with plurals and mass nouns, that is, nominal expressions that have cumulative reference, and as such introduce a scale of quantity. Some examples are given in (15).

This type includes many expressions that are based on a measure word, such as mountain, which both indicates high degree and provides information on, for instance, the shape of the quantity involved, or indicates a type of container. As one reviewer has noticed, it may not be fully appropriate to list these expressions as a separate category in the degree expression continuum, given that they may have different syntactic properties. However, Doetjes and Rooryck (2003) argue on the basis of agreement facts that une montagne de livres is structurally ambiguous between a structure in which une montagne is the head of the noun phrase (singular agreement with montagne) and another in which une montagne acts as amodifier and livres behaves like the head of the noun phrase (plural agreement with livres). In this second case une montagne may get a pure high degree interpretation and lose its lexical meaning of “a mountain” or “a stack.” It is this second use of une montagne that I am interested in here.

A further reason to treat this class here is that many degree expressions that are used outside of the nominal system start out historically as measure phrases indicating high degree of quantity in the nominal system. The lexical part of the interpretation of the measure word may bleach. Once the lexical meaning has entirely disappeared, these expressions often widen their distribution and may be used outside of the nominal system. An example is English a lot. In most cases where a lot is used, only the high degree meaning is left, and a lot has shifted towards a type D expression. A similar process seems to be going on with Dutch een hoop. It is marginally possible to say things such as?een hoop wandelen ‘to walk a lot.’ Other modifiers, such as een berg ‘a mountain’ are less easily used in a high degree reading in the nominal system, and cannot be used with verbs at all. Thus, ∗een berg wandelen ‘walk a mountain’ is completely excluded. French beaucoup and trop (type C) also illustrate this phenomenon, as they are etymologically derived from measure expressions. Beaucoup comes from beau ‘good’ and coup ‘blow’ while trop is etymologically related to troupeau ‘herd’ (for the historical development of beaucoup in French, see Marchello-Nizia 2006).

Type G expressions include, for instance, English many and few. They only combine with plural nouns, but they do have a clear degree interpretation. The existence of many and few seems to block the use of much and little with plural nouns. It is not completely clear how this type of blocking process works, as a lot combines with both plurals and mass nouns. French une foule in its pure high degree reading is also a case in point. The use of une foule with this interpretation is illustrated in (16), taken from Doetjes and Rooryck (2003). Its use with a mass term, as in ∗une foule de soupe, is excluded.

A further interesting member of class G is Dutch tig, which has recently been discussed in great detail by Norde (forthcoming). For most speakers of Dutch, tig, which has derived from the suffix -tig ‘-ty,’ as in twintig ‘twenty,’ may be used as a very high degree modifier of plural nouns, and is restricted to plural contexts. Examples are tig boeken ‘very many books,’ tig keer ‘again and again. Norde shows that some speakers also use tig as a degree modifier with other categories, including gradable adjectives and comparatives. Interestingly, the meaning of tig is one that is usually found for type B expressions. This may have been the reason for the confusion of tig ‘terribly many’ with ontzettend veel ‘terribly much/many,’ resulting in tig veel ‘a whole lot.’ In this form, tig is used as a modifier of veel, which in terms of degree modification behaves like a gradable adjective. This in turn might have been the source of further changes in the distribution of tig, which is attested not only with other gradable adjectives, as in tig leuk ‘extremely nice,’ but also with comparatives (tig sneller‘a whole lot faster), participles (tig bedankt ‘thanks a whole lot’), and with mass nouns (tig rotzooi ‘a whole lot of rubbish’). Even though the numbers of occurrences are so small that it is hard to judge on the basis of corpus information whether all predicted combinations are found, it seems that the use of tig as an intensifier has been at the source of an extension of its use in combination with other categories as well, and that the reason for the change is the unstable situation in which one and the same item acts like a type A and like a type G expression at the same time.

Norde assumes that the first step of the change was the analogy between veel and tig, both of which can modify plurals. As veel is also used with comparatives, the use of tig would have been extended to that context via syntactic reanalysis of [tig [betere oplossingen]] ‘a very large number of better solutions’ to [[tig betere] oplossingen] ‘far better solutions.’ This, in turn, might have been the source of the use of tig as an intensifier. As shown above, degree modification of adjectives and of comparatives is not similar in Dutch, so a change from a modifier of comparatives into a modifier of adjectives is not based on an analogy similar to the one causing the first step in the change. Moreover, it may be observed that tig veel is by far the most frequent context in which non-standard tig is used.6 This is not surprising if we assume that the (erroneous) use of tig veel replacing the original tig is at the origin of the other extensions, as I suggested above. In any case, tig seems to be an example of a type G expression that for some speakers has turned into a type C expression.

In the next subsection some particular characteristics of French très will be discussed, after which we will turn to a revised version of Table 1.

1 Degree expressions such as completely, fully, and half, which are associated with the presence of an endpoint on a scale or path, will not be taken into consideration. They differ in several respects from the modifiers looked at here, for instance in the fact that they can be used as path modifiers with PPs (Zwarts 2004). For discussion of the distribution of these expressions in various domains, see also Hoekstra (2004) and Vanden Wyngaerd (2001) (for verbs and event structure) and Kennedy and McNally (2005) (for adjectives).

2 In this chapter I will remain neutral about the syntax of these expressions. See Neeleman et al. (2004) and Doetjes (1997) for arguments in favor of the idea that expressions that only combine with adjectives and those that may modify other categories as well occupy different syntactic positions.

3 Next to these examples, the corresponding attributive adjectives may be used inside of a noun phrase:

In the Dutch example the presence of the adjectival agreement morpheme -e shows that verschrikkelijke is an attributive adjective and not an adverb (cf. 5a). Degree modification of this type, inside an argumental noun phrase containing a gradable noun, is limited to attributive adjectives corresponding to the type B expressions, and will be left out of consideration here.

4 Type A and type C roughly correspond to the class-1 and class-2 expressions in Neeleman et al. (2004).

5 Note that much and little are not used with plurals, which seems to be due to competition with many and few.

6 On the internet, tig veel is about fifty times more frequent than tig leuk, while veel is only four to five times as frequent as leuk. This is a very rough indication, based on Google searches.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)