Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Phonetic Transcription

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P1-C1

2025-02-18

1925

Phonetic Transcription

Because we are constantly involved with reading and writing in our daily lives, we tend to be influenced by the orthography when making judgments about the sounds of words. After all, from kindergarten on, the written language has been an integral part of our lives. Thus, it is very common to think that the number of orthographic letters in a word is an accurate reflection of the number of sounds. Indeed, this is the case for many words. If we look at the words pan, form, print, and spirit, for example, we can see the match in the number of letters (graphemes) with the number of sounds: three, four, five, and six, respectively. However, this match in number of graphemes and sounds is violated in so many other words. For example, both though and choose have six graphemes but only three sounds. Awesome has seven graphemes and four sounds, while knowledge has nine graphemes and five sounds. This list of non-matches can easily be extended to thousands of other words. These violations, which may be due to ‘silent letters’ or a sound being represented by a combination of letters, are not the only problems with respect to the inadequacies of orthography in its ability to represent the spoken language. Problems exist even if the number of letters and sounds match. We can outline the discrepancies that exist between the spelling and sounds in the following:

The same sound is represented by different letters. In words such as each, bleed, either, achieve, scene, busy, we have the same vowel sound represented by different letters, which are underlined. This is not unique to vowels and can be verified with consonants, as in shop, ocean, machine, sure, conscience, mission, nation.

The same letter may represent different sounds. The letter a in words such as gate, any, father, above, tall stands for different sounds. To give an example of a consonantal letter for the same phenomenon, we can look at the letter s , which stands for different sounds in each of the following: sugar, vision, sale, resume.

One sound is represented by a combination of letters. The underlined portions in each of the following words represent a single sound: thin, rough, attempt, pharmacy.

A single letter may represent more than one sound. This can be seen in the x of exit, the u of union, and the h of human.

One or more of the above are responsible for the discrepancies between spelling and sounds, and may result in multiple homophones such as rite, right, write, and wright. The lack of consistent relationships between letters and sounds is quite expected if we consider that the alphabet English uses tries to cope with more than forty sounds with its limited twenty-six letters. Since letters can only tell us about spelling and cannot be used as reliable tools for pronunciation, the first rule in studying phonetics and phonology is to ignore spelling and focus only on the sounds of utterances.

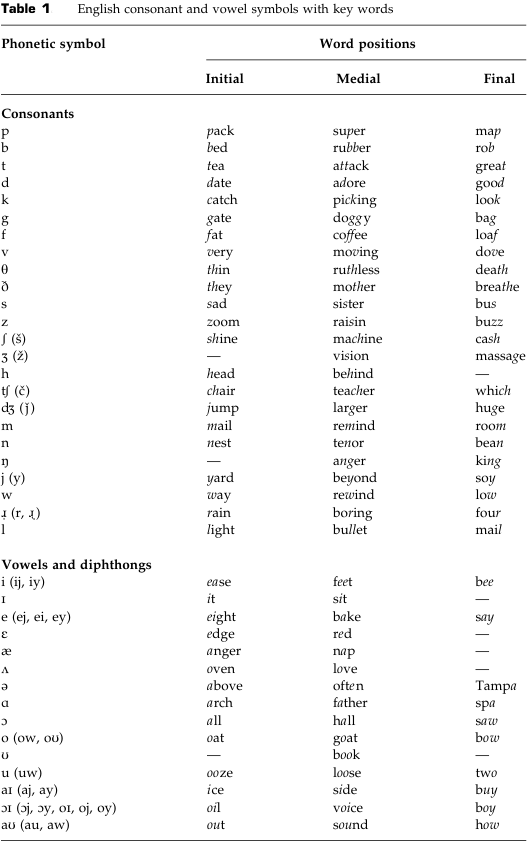

To avoid the ambiguities created by the regular orthography and achieve a system that can represent sounds unambiguously, professionals who deal with language use a phonetic alphabet that is guided by the principle of a consistent one-to-one relationship between each phonetic symbol and the sound it represents. Over time, several phonetic alphabets have been devised. Probably, the most widespread is the one known as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which was developed in 1888, and has been revised since then. One may encounter some modifications of some symbols in books written by American scholars. We will basically follow the IPA usage while pointing out common alternatives that are frequently found in the literature. First, we will present the symbols that are relevant to American English (see table 1) and later we will add some non-English sounds that are found in languages that our readership is likely to come in contact with.

The following should be pointed out to clarify some points about table 1 Firstly, certain positions that are left blank for certain sounds indicate the unavailability of vocabulary items in the language. Secondly, the table does not contain the symbol [ʍ] (or [hw], [W̥]), which may be found in some other books to indicate the voiceless version of the labio-velar glide. This is used to distinguish between pairs such as witch and which, or Wales and whales. Some speakers make a distinction by employing the voiceless glide for the second members in these pairs; others pronounce these words homophonously. Here, we follow the latter pattern. Finally, there is considerable overlap between final /j/ and the ending portion of /i/, /e/, /aɪ/, and /ɔɪ/ on the one hand, and between final /w/ of /o/, /u/, and /aʊ/ on the other. The alternative symbols cited make these relationships rather clear.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)