النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

β-HEMOLYTIC STREPTOCOCCI

المؤلف:

Cornelissen, C. N., Harvey, R. A., & Fisher, B. D

المصدر:

Lippincott Illustrated Reviews Microbiology

الجزء والصفحة:

3rd edition , p80-83

2025-01-01

995

S. pyogenes, the most clinically important member of this group of gram- positive cocci, is one of the most frequently encountered bacterial pathogens of humans worldwide. It can invade apparently intact skin or mucous membranes, causing some of the most rapidly progressive infections known. A low inoculum suffices for infection. Some strains of S. pyogenes cause postinfectious sequelae, including rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis. Nasopharyngeal carriage is common especially in colder months and particularly among children. Unlike staphylococcal species, S. pyogenes does not survive well in the environment. Instead, its habitat is infected patients and also normal human carriers in whom the organism resides on skin and mucous mem- branes. S. pyogenes is usually spread person to person by skin contact and via the respiratory tract.

A. Structure and physiology

S. pyogenes cells usually form long chains when recovered from liquid culture but may appear as individual cocci, pairs, or clusters of cells in Gram stains of samples from infected tissue. Structural features involved in the pathology or identification of group A streptococci include:

1. Capsule: Hyaluronic acid, identical to that found in human connective tissue, forms the outermost layer of the cell. This capsule is not recognized as foreign by the body and, therefore, is nonimmunogenic. The capsule is also antiphagocytic.

2. Cell wall: The cell wall contains a number of clinically important components. Beginning with the outer layer of the cell wall, these components include the following :

a. M protein: S. pyogenes is not infectious in the absence of M protein. M proteins extend from an anchor in the cell membrane, through the cell wall and then the capsule, with the N- terminal end of the protein exposed on the surface of the bacterium. M proteins are highly variable, especially the N-terminal regions, resulting in over 80 different antigenic types. Thus, individuals may have many S. pyogenes infections throughout their lives as they encounter new M protein types for which they have no antibodies. M proteins are antiphagocytic and they form a coat that interferes with complement binding.

b. Group A-specific C-substance: This component is composed of rhamnose and N-acetylglucosamine. [Note: All group A streptococci, by definition, contain this antigen.]

c. Protein F (fibronectin-binding protein) mediates attachment to fibronectin in the pharyngeal epithelium. M proteins and lipo- teichoic acids also bind to fibronectin.

3. Extracellular products: Like Staphylococcus aureus, S. pyogenes secretes a wide range of exotoxins that often vary from one strain to another and that play roles in the pathogenesis of disease caused by these organisms .

B. Epidemiology

The only known reservoir for S. pyogenes in nature is the skin and mucous membranes of the human host. Respiratory droplets or skin contact spreads group A streptococcal infection from person to person, especially in crowded environments such as classrooms and children's play areas.

C. Pathogenesis

S. pyogenes cells, perhaps in an inhaled droplet, attach to the pharyngeal mucosa via actions of protein F, lipoteichoic acid, and M protein. The bacteria may simply replicate sufficiently to maintain themselves without causing injury in which case the patient is then considered colonized . Alternatively, bacteria may grow and secrete toxins, causing damage to surounding cells, invading the mucosa, and eliciting an inflammatory response with attendant influx of white cells, fluid leak- age, and pus formation. The patient then has streptococcal pharyngitis. Occasionally, there is sufficient spread that the bloodstream is significantly invaded, possibly resulting in septicemia and/or seeding of distant sites, where cellulitis (acute inflammation of subcutaneous tissue), fasciitis (inflammation of the tissue under the skin that covers a surface of underlying tissue), or myonecrosis (death of muscle cells) may develop rapidly or insidiously. However, direct inoculation of skin from another person's infection is probably more common as the pathogenesis of streptococcal skin and soft tissue infection.

D. Clinical significance

S. pyogenes is a major cause of cellulitis. Other more specific syndromes include:

1. Acute pharyngitis or pharyngotonsilitis: Pharyngitis is the most common type of S. pyogenes infection. S. pyogenes pharyngitis ("strep throat") is associated with severe, purulent inflammation of the posterior oropharynx and tonsillar areas . [Note: If a sunburn like rash develops on the neck, trunk, and extremities in response to the release of pyrogenic exotoxin to which the patient does not have antibodies, the syndrome is designated scarlet fever.] Many strep throats are mild, and many sore throats caused by viruses are severe. Hence, laboratory confirmation is important for accurate diagnosis and treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis, particularly for the prevention of subsequent acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease.

2. Impetigo: Although S. aureus is recovered from most contemporary cases of impetigo , S. pyogenes is the classic cause of this syndrome. The disease begins on any exposed surface (most commonly, the legs). Typically affecting children, it can cause severe and extensive lesions on the face and limbs . Impetigo is treated with a topical agent such as mupirocin, or systemically with penicillin or a first-generation cephalosporin such as cephalexin, which are effective against both S. aureus and S. pyogenes.

3. Erysipelas: Affecting all age groups, patients with erysipelas experience a fiery red, advancing erythema, especially on the face or lower limbs .

4. Puerperal sepsis: This infection is initiated during, or following soon after, the delivery of a newborn. It is caused by exogenous transmission (for example, by nasal droplets from an infected carrier or from contaminated instruments) or endogenously, from the mother's vaginal flora. This is a disease of the uterine endometrium in which patients experience a purulent vaginal discharge and are systemically ill.

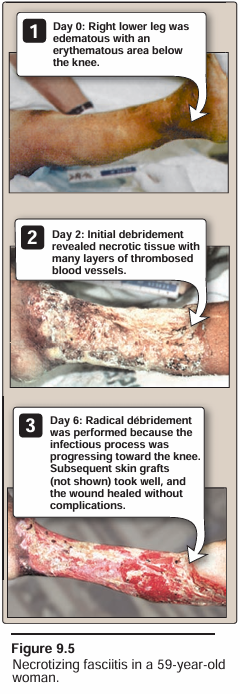

5. Invasive group A streptococcal disease: Common during the first half of the century, invasive group A streptococcal (GAS) disease became rare until its resurgence during the past decade. Patients may have a deep local invasion either without necrosis (cellulitis) or with it (necrotizing fasciitis/myositis) as shown in Figure 9.5. [Note: The latter disease led to the term "flesh-eating bacteria."] Invasive GAS disease often spreads rapidly, even in otherwise healthy individuals, leading to bacteremia and sepsis. Symptoms may include a toxic shock-like syndrome, fever, hypotension, multiorgan involvement, a sunburnlike rash, or a combination of these symptoms.

6. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: This syndrome is defined as isolation of group A β-hemolytic streptococci from blood or another normally sterile body site in the presence of shock and multiorgan failure. The syndrome is mediated by the production of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins that function as superantigens causing massive, nonspecific T-cell activation and cytokine release. Patients may initially present with flulike symptoms, followed shortly by necrotizing soft tissue infection, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and renal failure. Treatment must be prompt and includes antistreptococcal antibiotics, usually consisting of high-dose penicillin G plus clindamycin.

7. Post-streptococcal sequelae

a. Acute rheumatic fever: This autoimmune disease occurs 2 to 3 weeks after the initiation of pharyngitis. It is caused by cross- reactions between antigens of the heart and joint tissues, and the streptococcal antigen (especially the M protein epitopes). It is characterized by fever, rash, carditis, and arthritis. Central nervous system manifestions are also common including Sydenham's chorea, symptoms of which are uncontrolled movement and loss of fine motor control. Rheumatic fever is preventable if the patient is treated within the first 10 days following onset of acute pharyngitis.

b. Acute glomerulonephritis: This rare, postinfectious sequela occurs as soon as 1 week after impetigo or pharyngitis ensues, due to a few nephritogenic strains of group A streptococci. Antigen-antibody complexes on the basement mem- brane of the glomerulus initiate the disease. There is no evidence that penicillin treatment of the streptococcal skin dis- ease or pharyngitis (to eradicate the infection) can prevent acute glomerulonephritis.

E. Laboratory identification

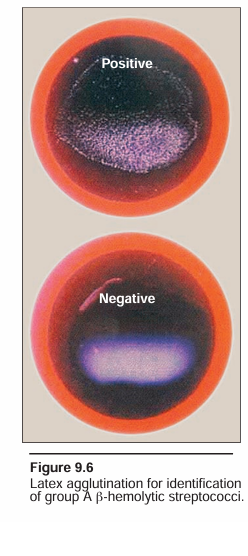

Rapid latex antigen kits for direct detection of group A streptococci in patient samples are widely used. In a positive test, the latex particles clump together, whereas in a negative test, they stay separate, giving the suspension a milky appearance (Figure 9.6). These tests have high specificity but variable sensitivity compared with culture techniques. Specimens from patients with clinical signs of pharyngitis and a negative antigen detection test should undergo routine culturing for streptococcal identification. Depending on the form of the disease, specimens for laboratory analysis can be obtained from throat swabs, pus and lesion samples, sputum, blood, or spinal fluid. S. pyogenes forms characteristic small, opalescent colonies sur- rounded by a large zone of β hemolysis on sheep blood agar . [Note: Hemolysis of the blood cells is caused by steptolysin S, which damages mammalian cells resulting in cell lysis.] This organism is highly sensitive to bacitracin, and diagnostic disks with a very low concentration of the antibiotic inhibit growth in culture . S. pyogenes is also catalase negative and optochin resistant. Group A C-substance can be identified by the precipitin reaction. Serologic tests detect a patient's antibody titer to streptolysin O (ASO test) after group A streptococcal infection. Anti-DNase B titers (ADB test) are particularly elevated following streptococcal infections of the skin.

F. Treatment

Antibiotics are used for all group A streptococcal infections. S. pyogenes has not acquired resistance to penicillin G, which remains the antibiotic of choice for acute streptococcal disease. In a penicillin- allergic patient, a macrolide such as clarithromycin or azithromycin is the preferred drug . Penicillin G plus clindamycin are used in treating necrotizing fasciitis and in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Clindamycin is added to penicillin to inhibit protein (i.e., toxin) synthesis so that a huge amount of toxin is not released abruptly from rapidly dying bacteria.

G. Prevention

Rheumatic fever is prevented by rapid eradication of the infecting organism. Prolonged prophylactic antibiotic therapy is indicated after an episode of rheumatic fever, because having had one episode of this autoimmune disease in the past is a major risk factor for subsequent episodes if the patient is again infected with S. pyogenes.

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)