تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

NUCLEAR FORCE

المؤلف:

E. R. Huggins

المصدر:

Physics 2000

الجزء والصفحة:

554

16-12-2020

1962

NUCLEAR FORCE

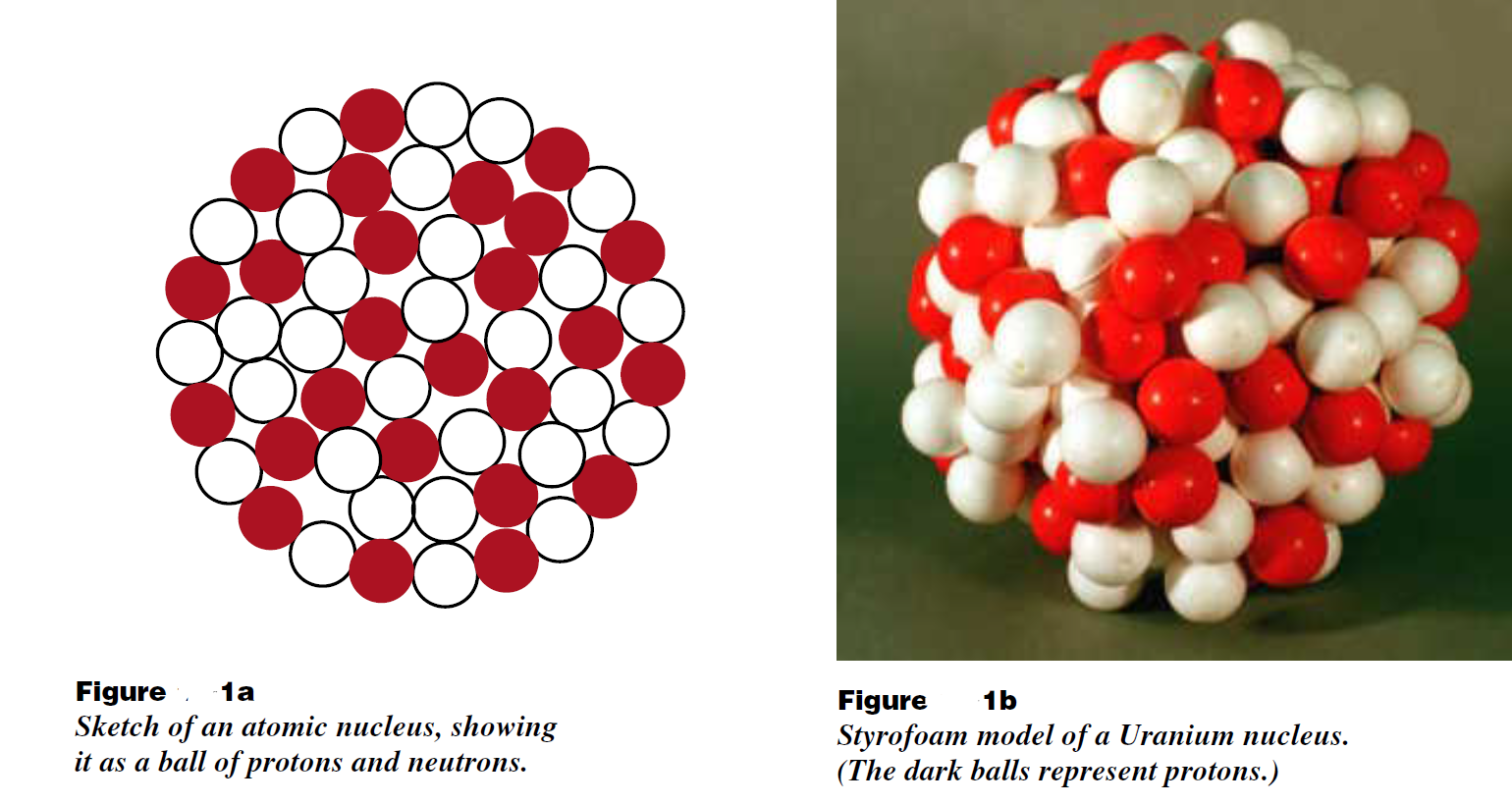

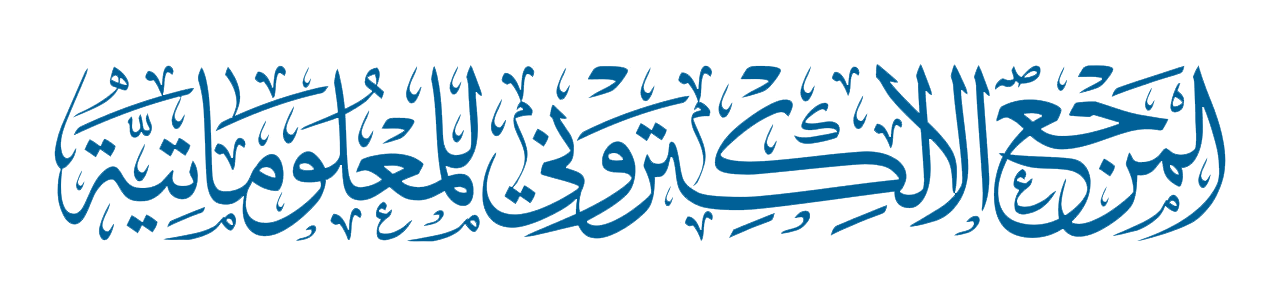

In 1912 Ernest Rutherford discovered that all the positive charge of an atom was located in a tiny dense object at the center of the atom. By the 1930s, it was known that this object was a ball of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons packed closely together as illustrated in Figure (1) reproduced here. Protons and neutrons are each about 1.4 × 10– 13 cm in diameter, and the size of a nucleus is essentially the size of a ball of these particles. For example, iron 56, with its 26 protons and 30 neutrons, has a diameter of about 4 proton diameters. Uranium 235 is just over 6 proton diameters across. (One can check, for example, that a bag containing 235 similar marbles is about six marble diameters across.)

That the nucleus exists means that there is some force other than electricity or gravity which holds it together. The protons are all repelling each other electrically, the neutrons are electrically neutral, and the attractive gravitational force between protons is some 10 – 38 times weaker than the electric repulsive force. The force that holds the nucleus together must be attractive and even stronger than the electric repulsion. This attractive force is called the nuclear force.

The nuclear force treats protons and neutrons equally. In a real sense, the nuclear force cannot tell the difference between a proton and a neutron. For this reason, we can use the word nucleon to describe either a proton or neutron, and talk about the nuclear force between nucleons. Another feature of the nuclear force is that it ignores electrons. We could say that electrons have no nuclear charge.

The properties of the nuclear force can be deduced from the properties of the structures it creates—namely atomic nuclei. The fact that protons and neutrons maintain their size while inside a nucleus means that the nuclear force is both attractive and repulsive. Try to pull two nucleons apart and the attractive nuclear force holds them together, next to each other. But try to squeeze two nucleons into each other and you encounter a very strong repulsion, giving the nucleons essentially a solid core.

We have seen this kind of behavior before in the case of molecular forces. Molecular forces are attractive, holding atoms together to form molecules, liquids and crystals. But if you try to push atoms into each other, try to compress solid matter, the molecular force becomes repulsive. It is the repulsive part of the molecular force that makes solid matter hard to compress, and the repulsive part of the nuclear force that makes nuclear matter nearly incompressible.

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاب (سر الرضا) ضمن سلسلة (نمط الحياة)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاب (سر الرضا) ضمن سلسلة (نمط الحياة)