النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 15-11-2020

Date: 9-12-2015

Date: 3-12-2015

|

CHO Cells

1. Origin

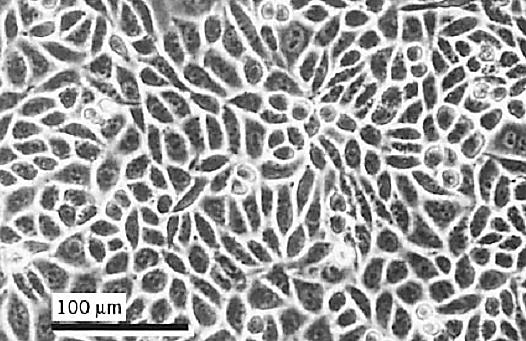

CHO cells were originated as a cell line by Theodore Puck in 1958 (1) from the Chinese hamster, Cricetulus griseus. CHO/Pro cells requiring proline for growth were subsequently derived by nutritional selection. The parental cells were treated with bromodeoxyuridine in proline-deficient medium and then exposed to the near-visible UV from a fluorescent light. This killed the growing cells, but not those that required proline. Proline-requiring clones were then grown up by feeding the surviving cells with proline-rich medium. CHO/Pro– was subcloned by dilution cloning, and cell line CHO/Pro-K1 was isolated. The current designation of this cell line in common use is CHO-K1, and it still has a requirement for proline, which is present in Ham's F12, the medium usually recommended for its propagation. It is listed in the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) catalogue as CCL-61 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Confluent culture of CHO-K1 cells. Phase contrast, Olympus CK microscope, 20× objective.

2. Properties

CHO-K1 (Fig. 1) is a continuous cell line and near-diploid with 20 chromosomes (2C = 22). It has a very short doubling time of around 15 h, making it popular as a host for transfection and biotechnology. The plating efficiency is also very high, and can be 100% under optimal conditions, so these cells have always been popular for clonogenic survival studies of nutritional mutants and radiation survival. Chinese hamster cells originally became popular for genetic studies because of their relatively small number of readily distinguishable chromosomes, but the advent of chromosome banding techniques and chromosome painting by fluorescence in situ hybridization makes the distinction of individual chromosomes easier in many other species.

CHO-K1 cells, although transformed, still retain nutrient-dependent G1 cell-cycle blockade. Isoleucine deprivation blocks the cells in G1, and its restoration generates a synchronous population (2) .

3. Usage

CHO-K1 cells have been used in cell-cycle control and signaling (3) and are used extensively in biotechnology (4). They are used frequently in DNA transfection (5) and virally mediated DNA transfer (6). They can be maintained in suspension culture to generate large numbers of cells or product. Using methotrexate-induced co-amplification with cotransfected dihydrofolate reductase, they have been used for production of interferon-g (7) and prothrombin-2 (8). They have been adapted to grow in serum-free medium (9). Together with V79 cells, another Chinese hamster cell line, they have been used extensively in genotoxicity studies (10).

References

1. T. T. Puck, S. J. Cieciura, and A. Robinson (1958) J. Exp. Med. 108, 945–956.

2. K. D. Ley and R. A. Tobey (1970) J. Cell. Biol. 47, 453–459.

3. G. Tortora, S. Pepe, C. Bianco, V. Damiano, A. Ruggiero, G. Baldassarre, C. Corbo, Y. S. Chochung, A. R. Bianco, and F. Ciardiello (1994) Intl. J. Cancer 59, 712–716.

4. K. B. Konstantinov (1996) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 52, 271–289.

5. S. Subramanian and F. Srienc (1996) J. Biotechnol. 49, 137–151.

6. T. Schoneberg, V. Sandig, J. Wess, T. Gudermann, and G. Schultz (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 100 1547–1556, .

7.V. Leelavatcharamas, A. N. Emery, and M. Al-Rubeai (1994) Cytotechnology 15, 65–71.

8. G. Russo, A. Gast, E. J. Schlaeger, A. Angiolillo, and C. Pietropaolo (1997) Protein Express. Purif. 10, 214–225.

9. M. J. Keen and N. T. Rapson (1995) Cytotechnology 17, 153–163.

10. H. F. L. Mark, R. Naram, T. Pham, K. Shah, L. P. Cousens, C. Wiersch, E. Airall, M. Samy, K. Zolnierz, R. Mark, K. Santoro, L. Beauregard, and P. H. Lamarche (1994) Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 24, 387–395

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بمناسبة مرور 40 يومًا على رحيله الهيأة العليا لإحياء التراث تعقد ندوة ثقافية لاستذكار العلامة المحقق السيد محمد رضا الجلالي

|

|

|